Epistemic Intolerance is Sophicidal

We need to revive the ecumenical spirit that gave impetus to science in the 20th century

It is a common occurrence to hear echoes of vociferous and indignant shouts whenever a new study is proclaimed with the object of reminding us of the influences of the “First World” upon the epistemological and ontological life-worlds of former colonies. Now it is expected that our ears attend solely to those voices whose words have rarely been committed to paper—the voices of those who once declared their right to partake in the circulation of ‘grand ideas’, to be heard as they ought. It is for the sake of truth that we have granted them the attention so long denied. Only the most ingenuous—or indeed the most dishonest—of theorists would ignore that many of these ‘great ideas’ attained undeniable relevance not by the veracity of their unyielding message or the merit of their inspiring rhetoric, but merely by receiving, as if by a loan of deference, the prestige acquired by virtue of (or perhaps by the vices of) the power wielded by the groups that advocated them. Two hundred and fifty years past, Adam Smith, for instance, postulated that the sole explanation for the triumph of such controversial mercantilist economic theses in the policy-making circles of his day was that they were meant to serve the interests of those who already held power and held it tight.

But if it is, therefore, indispensable that research should adopt a sceptical stance toward any discourse or approach that inherits the blind spots of hegemonic investigative traditions, it would seem most absurd to caution that care must be taken lest we cast the baby out with the dirty bathwater! For if attending to issues once long neglected prevents us from suffering intellectual thirst — as a fountain that gushes from within and nourishes the spirit — the spring itself still requires a proper bed of water, a fundamental reservoir to sustain it.

The force of the sciences only grows when we unite the traditional fields of study — which still prove themselves as terrains of great fertility — with heterodox research, not as a perfect substitute but as an essential complement. It is by that very joining, like a bond of solidarity that fastens the division of intellectual labour, that our understanding of the human condition is elevated; yet one must ever exercise prudence when turning to grand novelties, for an undue attachment to the new may too readily degenerate into a compulsive frenzy, the very fatal opposite of misoneism. Were the interest in the Whole to fragment, then the motivation that impels us to explore its parts would crumble in its wake. Thus, nothing substantial founded upon interminable innovation whilst forsaking its roots endures — the tree may branch, but its boughs wither, for the roots have ceased to find water for the sap. Behold, a forest petrifies, the whistling winds cease to caress verdant leaves and accomplish little more than to rustle dry twigs: nothing survives the desertification of curiosity!

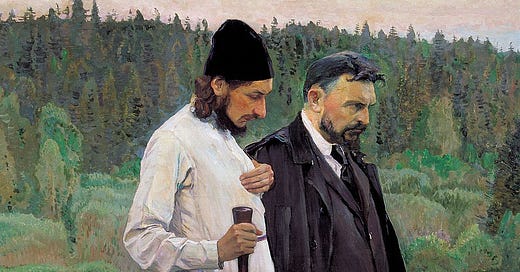

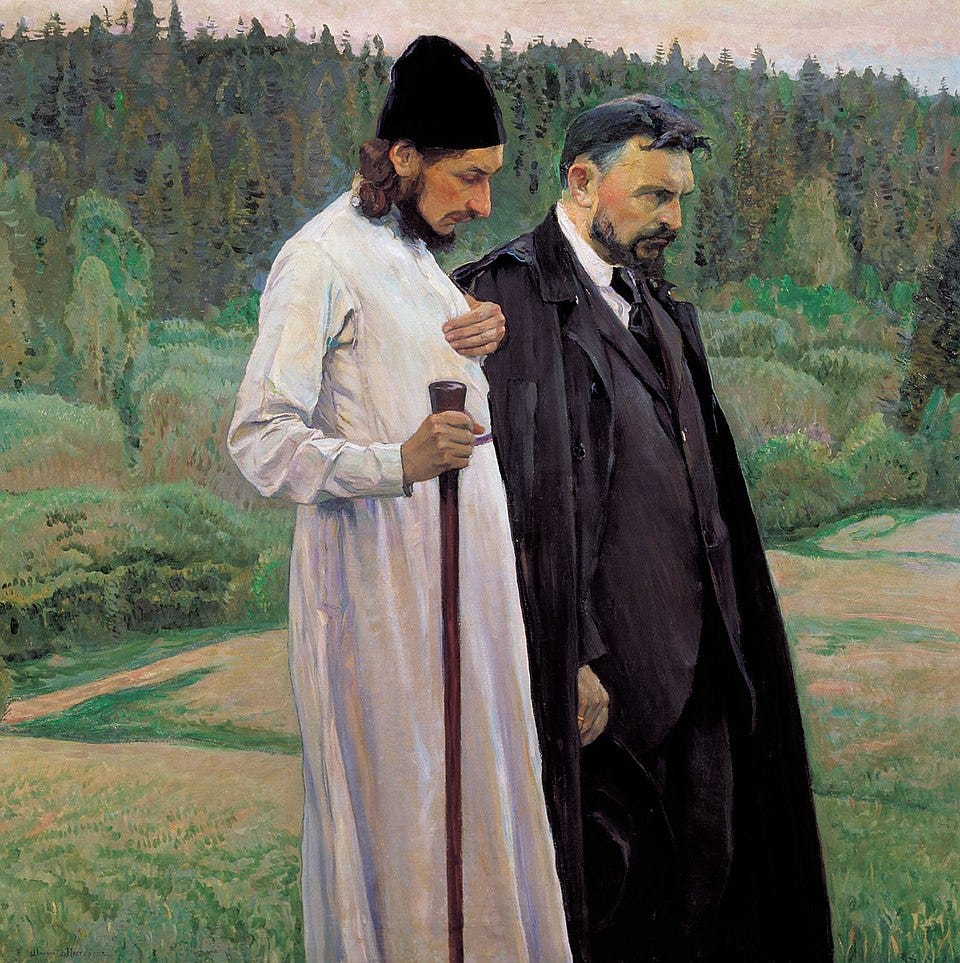

Were I permitted to append a wholly subjective note on the fundamental error of this puerile disposition — for in fact it is the very lot of youth to be ever in flight — I would venture to cite the perspective of Sergei Bulgakov, that eminent theologian of the Catholic-Orthodox tradition who commenced his intellectual career with a treatise on the Philosophy of Economy. Insofar as I comprehend his thought, he would aver that if God were ever to lose interest in our experiences, in the radical renewal of the human condition which each of us enacts merely by living — since we are, each one, vanguardists in the art of life — then we would be deprived of any purpose. The divine consciousness, inherently omnipotent, omnipresent and omniscient, created us freely in Liberty so that It might, through us, become, so to speak, “omnicognoscente:”

The world as cosmos and the empirical world, Sophia and humanity, maintain a living interaction, like a plant’s nourishment through its roots. Sophia, partaking of the cosmic activity of the Logos, endows the world with divine forces, raises it from chaos to cosmos. Nature always perceives her reflection in man, just as man, despite his faults, always perceives his own reflection in Sophia. Through her he takes in and reflects in nature the wise rays of the divine Logos; through him nature becomes sophic. Such is this metaphysical hierarchy. This resolves the puzzle of human creativity, for in all fields — in knowledge, economy, culture, art —it is sophic, that is, it partakes of the divine Sophia. Man’s participation in Sophia, which brings the divine forces of the Logos to the world and plays the role of natura naturans toward nature, makes human creativity possible. Man can ‘‘conquer’’ nature only insofar as he potentially contains all of nature within himself; he comes to possess nature in the process of realizing this potential. Thus, as Plato pointed out, knowledge is really remembrance—not in the theosophical sense of remembrance of past lives but metaphysically. Human creativity is really a re-creation of that which preexists in the metaphysical world; it is not creation from nothing but replication of something already given, and it is creative only insofar as it is free re-creation through work (Sergei Bulgakov, 2000 [1912] p. 145).

I have in mind studies that attend either to the contributions of intellectuals belonging to societies which, in days gone by (or even if not much so), occupied the very zenith of the hierarchies wrought by the process of globalisation over these past centuries, or even to ideas emerging from the metropolitan context that have exerted an enormous influence upon the formation of modern societies. Such themes have been relatively stigmatised, as though they signified a choice most unjust and illegitimate in the face of the perennial scarcity of time and resources that delineates the borders of intellectual production in every age. But universities are no factories and professors can only be said to be proletarians in the original sense of proletarii, “maker of offspring”: and babies — may God grant us so — will never be mere commodities.

The predilection, nowadays, for studies concerning thought-matrices — supposedly indigenous or even autochthonous — or for the legacy of concepts wrought “from below upward,” from the margins to the centre, appears to oscillate, ambivalently, between a healthy and enriching scepticism (with the potential to open our eyes to new investigative horizons) and a moralistic juvenility of an almost, if not entirely, accusatory tone which, by virtue of the inherent vagueness of its structuralist imputation, refuses to single out any clear malefactors, thereby assailing an entire heritage for its influence upon the unconscious.

The contradiction intrinsic to this misbegotten disposition — when pursued through the tortuosities of a poorly defined moralism — is that its accused are rendered, by principle, beyond reproach for any of the ensuing consequences. Such critique, I venture, bears a value of negative import for the Republic of the Sciences, as Pierre Bourdieu was fond of declaring; for, like nearly every iconoclastic outcry, it proves counterproductive and intolerant, affording us both the slight unfastening of windows long barred though in a newly erected confinement within a tall tower of arrogance. In so doing, it is we who lose that which is essential: the subtle nuances without which one cannot hope to fathom the fragile and capricious edifices of belief and identity born of human encounter.

Ecumenism was the very motoring spirit of academic aspiration throughout the Twentieth Century. A modernist aura hung, almost equally, over both the most demure and traditional centres of learning as well as over the burgeoning poles of technology. The education of engineers, computer scientists, physicians, and many other degrees which on first impression seemed more devoted to techné than to arché, prized not for intrinsic and self-referential ends but for their social utility, was nevertheless governed by curricula that assumed their pupils to be worthy recipients of a truly liberal education, whilst the Humanities were apprehended as a grand dialogue extracting from an entire civilisational heritage that vital capacity for self-critique which sustains it.

This, however, does not imply that the Twentieth Century itself — that interval stretching from 1900 to 1999 — was an epoch worthy of such veneration due to a universal reproduction of moral egalitarianism as to underwrite the grand heroism of absolute solidarity. In truth, the “Brief Twentieth Century” was defined by a zeitgeist that defies mere chronology: it was the century both of the ascent and decline of the élan vital and of the transhistorical reformation heralded by Vatican II; it was the century of Foucault and of Oakeshott, of Pocock and of Latour, of Maritain and Tawney, of Sartre and of Camus, of Pessoa and of Joyce; it was the century during which Europe was gradually provincialised and the universal inheritance of human civilisation radically reappropriated by non-Europeans. By definition, the Twentieth Century is the age of all the great thinkers in the human tale, from Plato to Marx. In a certain measure, it was an era of continual rebaptisms and of renaissances in the purest sense. Ortega y Gasset was by no means mistaken in asserting that the age of the “mass-man” was not one of decline but a high juncture where successive syntheses reached their apotheosis upon the peak of temporal dialectics.

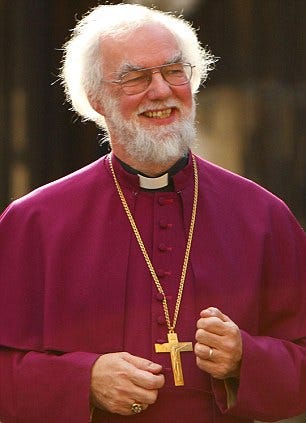

There is no mere note of nostalgia in me for an idyllic past — yet within me there burns a profound hunger for that vintist spirit. Deep down, we are never fully free of it! The Twentieth Century has traversed the years after 2000 with scant heed for the dictates of the Gregorian calendar; yet it now appears to have become a farce, a pastiche of itself, a clumsily wrought caricature of its innate potential, having withered in the wake of a widespread disbelief in sapere aude, that exalted ideal both noble and prodigious which entered the world not with the sweetness and humility so befitting, but with the Will to Power that so oppressed the silent wars that were mischaracterized as ‘peaceful’ during the Long Nineteenth Century. It now awaits its counterpoint, that elusive voice which may yet breathe life anew and captivate all; and it is no mere accident that the Twenty-First Century, still bereft of its own identity, is henceforth deemed the Century of Pope Francis, of Primate Michael Curry, of Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I, and of Archbishop Rowan Williams!

The Academy, contrary to what many had once envisioned it should be, has steadily lost that truly Modern (and, indeed, divine) essence which was so dear to it and which ennobled, as never before, that medieval institution born much as a monastery, ever in tension with its surroundings. The phenomenon is akin to that of Modern Art, which gradually gave way to a modernism that amounted to nothing more than the affectation of outsiders preferring to fashion their isolated, condescending bubbles, a detached society turned inward in lifeless museums and languid expositions.

The University, for its part, has become a space of unseemly arrogance — not because its members exhibit any particular moral failing, but simply because, as an institution, it has come to represent an Aristocracy tragically out of place, indifferent to both excellence and merit, sustained solely by the obstinate refusal of those who, in denying the conditions whence they were born, have resolved to cease transforming the world, thereby rendering the universitas, in an ironic twist, a self-contained renunciation of the very rules governing social life outside its walls. Whereas once it was the solemn duty of the University — as it was of the Church — to signal Virtue through an active participation in communal life (regardless of how successful any mundane cooperation might be), it is now to be feared that the University is failing to provide signs pointing toward any ethical Revelation, it is to be feared that it will no longer indicate the possibility of a Higher Life, one more beautiful, more exalted, and more precious, doing so not through words but by deeds, rather becoming nothing but another therapeutic circle that promotes solely the self-affirmation of its own members and remains inaccessible and uninspiring to those who view it from afar.

What I dread is that these new modalities of epistemic intolerance — paradoxically derived from one of the most illustrious impulses of the Twentieth Century, namely, the active tolerance and dialogical inclusion — might degenerate into a veritable sophicide. Without Universal Charity, striped from that uncalculated, interpersonal and fully accessible Love, the new generations may cease to be actually creative, turning into sheer replicators of the very distances we once yearned, with such intimacy, to surmount. In such dire circumstance, we might only rely upon a deus ex machina to deliver us Salvation instead of being granted another genuine “solution.” From the cogs of an “industry of ideas,” the only unforeseen outputs become the malfunctions, the stillborn products, the unsaleable commodities — utter rubbish.

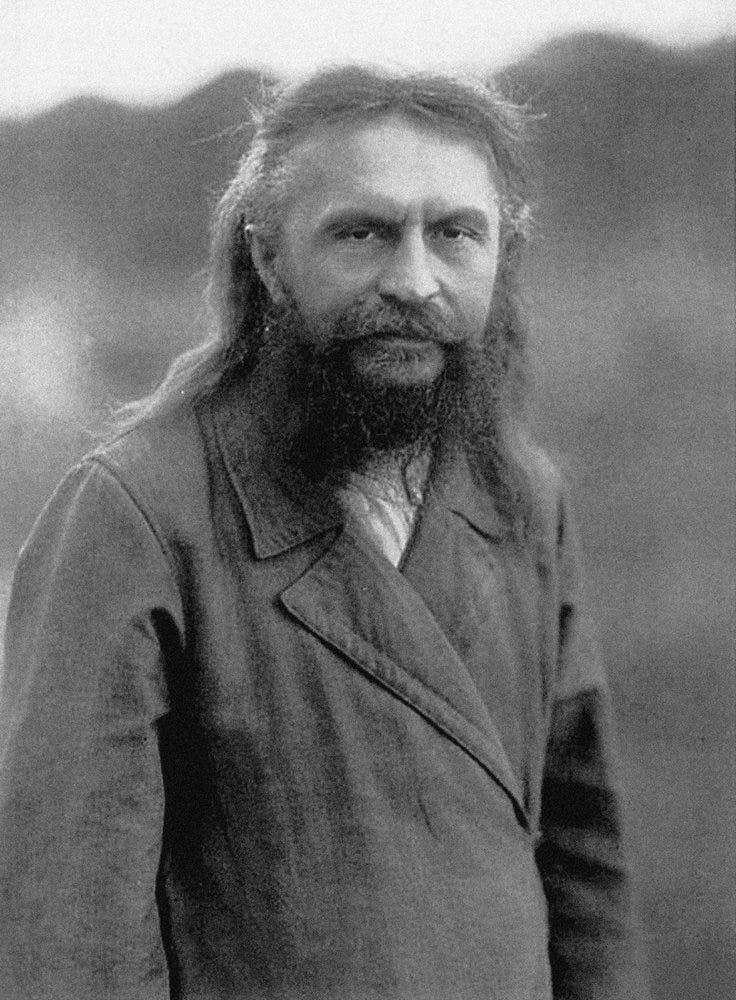

In the subterranean recesses of bitterness — in that sector of the factory where no lamp is now required, for no soul is to be seen, where labouriousness has driven the productivist ideology until the apex of its own logic and, thereby, has exterminated valuable work — there can be no regenerative solitude akin to that of Pavel Florenski:

I am alone, absolutely alone in the whole world. But my sorrowful loneliness aches sweetly in my heart. At times, it seems that I have become one of those leaves that are whirled about by the wind on paths. I rose today in the early morning and seemed to sense something new. Indeed, in a single night the back of summer had been broken. Golden leaves whirled over the ground in serpentine, wind-driven eddies. Flocks of birds were set in motion. There were files of cranes, and a swirling of crows and daws. The air was filled with the cool aroma of autumn, the smell of decaying leaves, a longing for the distances. I went out to the edge of the woods. One after another, one after another, leaves were falling to earth. Like dying butterflies, they were describing slow circles in the air as they de scended to earth. On the fallen grass the wind was playing with the “liquid shadows” of tree limbs. How good it was, how joyous and sad! … It seems that my whole soul is melting in sweet agony at the sight of these fluttering leaves as I smell the fragrance of faded aspen groves. It appears that the soul finds itself in seeing this death, that it has a foretaste of resurrection in this fluttering. Seeing death! I am surrounded by it. … Again and again, every sin, every “petty” baseness is present, ineradicably distinct, in my consciousness. More and more deeply, “petty” inattentions, egotism, and heartlessness are branded into the soul with letters of fire, gradually crippling it. Not that there was ever anything clearly bad, anything clearly, tangibly sinful. But always (always, O Lord!) it was in the petty things. And out of petty things, mountains grew! And looking back, one can see nothing but foulness. … Everything whirls. Everything slides into death’s abyss. Only One abides, only in Him are constancy, life, and peace. … Outside of this One Center, “the only certain thing is that nothing is certain and that there is nothing more miserable or arrogant than man.” … Yes, in life everything is in a state of unrest, every thing is as unstable as a mirage. And out of the depths of the soul there rises an unbearable need to find support in the “Pillar and Ground of the Truth” (1 Tim. 3:15) … not in just one of the truths, not in one of the particular and fragmented human truths, which are unstable and blown about like dust chased by the wind over mountains, but in total and eternal Truth, the one Divine Truth, the radiant and celestial Truth, that “Truth” which, according to the ancient poet, is the “sun of the world” (Pavel Florensky, 1997 [1914], pp. 11-12).

Within the metaphysics of Love also resides the foundations of true epistemology. Agape holds preeminence in the ontological hierarchy of the human Will; it is she who guides both Eros and Philia beyond the fetters of encapsulated experience. Love is neither partisan nor divisible; by its very nature it defies contingency — it is a ceaselessly flowing stream, and even when it appears to stagnate — as in the case of lakes, it is but new bodies of water ever reformed and renewed, interlinked through the heavens and with the earth to the Ocean that permeates it all. As Charles Péguy so beautifully recorded in his Memoirs of Youth, any institution that aspires to endure must transcend the shallow interests, the mere plans, and the envisioned goals, if it is to prevail; no institution is born aloft through time solely by the objectives it aims to fulfil, just as our hearts beat not solely for the purpose of spending energy away.

The raison d'être of the University does not reside in “producing science,” nor in “changing the world”; it is not found in its social mission, nor in its economic contribution; it lies not even in keeping alight the torch of civilisation — although all these noble incumbencies are almost inextricably entwined with it. No, that which sustains it — and that which shall keep it alive — can never derive from without; it must come from within, as the Breath of the Spirit, a self-justifying activity yet by no means self-enclosed; its very being springs from the scholarly endeavour that makes the University what it is. And there is no practice more liberal than Education — the primordial principle of all Science. Political Economy, in its limited scope, is naught when set against the Divine Œconomia:

Everything begins in mysticism and ends in politics. The interest, the question, the essential is that in each order, in each system, mysticism be not devoured by politics to which it gave birth. Politics laughs at mysticism; nevertheless it is still mysticism which feeds these same politics (Charles Péguy, 2001).

If the Value of all our endeavours can truly be found only in the Whole, then pluralism is of itself inherently precious. Modernity is, in truth, a Divine Symphony. We must not permit its most heroic and transcendent ideals to be betrayed by a cowardly retreat from the world, from all its dilemmas and imperfections; neither can we allow it to be subverted by an intolerance toward the Dialectic that subsumes every event. If the Spirit of the Twentieth Century yet remains discernible about us, let us strip it of its vestments of farce and, instead, stage a new, redemptive Tragedy. Let us pray together that from the current solitude, from segregated circles and incommunicable bubbles, may arise a renewed hunger for Social Life, a fresh thirst for Communion, and an unyielding new Love. Let us honour Sophia with our Freedom and Fraternal Solidarity. And let us not extinguish within ourselves that Love without which no true knowledge is attainable, for without it we are utterly incapable of grappling with our own insecurities. Let us eschew sophicidal ideations at all cost.

Amen.

Bibliography

Charles Péguy (2001), Temporal and Eternal, Liberty Fund, Indiana.

Pavel Florensky (1997 [1914]), The Pillar and Ground of the Truth: An Essay in Orthodox Theodicy in Twelve Letters, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Sergei Bulgakov (2000 [1912]), Philosophy of Economy: The World as a Household, Yale University Press, New Haven.