François Perroux and the ❝heritage of human civilization❞ (II)

A brief intellectual history of the Perrouxian notion of development

*Today’s text includes subsections 2.1 and 2.2; next Friday, I will post sections 2.3 and 2.4, finally finishing the brief intellectual history of Perroux’s development theses*

2. Background of Perroux’s Theory of Development

Perroux, whilst pursuing his doctoral studies, was under the tutelage of René Gonnard, the author of a work of some renown at the time, Histoire des Doutrines Économiques (1921). His dissertation did address itself to the ‘problem of profit determination,’ drawing, it would appear, in the main from Italian, German, and Austrian sources – lands wherein corporatist thought, then waxing in influence, burgeoned in opposition alike to the ‘communism’ of the Russian Revolution and to the ‘libertarian’ Capitalism of the West. Having attained his degree, Perroux was thereafter honoured with a most prestigious bursary from the Rockefeller Fellowship in the year of 1934. Instead of voyaging to the United States, as was the common lot of Rockefellers, he took the audacious decision to remain upon the Continent, employing his funds for an intellectual sojourn through Rome, Berlin, and Vienna, where he would bear witness, at close quarters, to the ascent of fascist corporatism. We shall discourse upon this matter in fuller measure in section 2.2; yet first, let us weave a contrast betwixt the prevailing theories of development to which Perroux, from his younger days, did intend to set himself in opposition.

2.1 Against Perfect Equilibria

This present section is intended merely as an elucidation, contextualising not the antecedents of Perroux’s own theory, but rather those anterior theses against which it was formulated. It shall be founded upon a lengthy, yet brilliant, exposition by Hirschman, in his The Strategy of Economic Development (1958), a tome which directly cites Perroux, and which received from the French author’s hand copious commendations in their exchange of correspondence.

In the opening years of the 1940s, Welfare Economics garnered ever-increasing attention. The Second World War did transform the ‘world into a stage’:

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages.

William Shakespeare, As You Like It (1623)

The spectacle, howsoever, was an absurdity. A veritable insanity. Never before had mankind, as a whole, been so starkly compelled to perceive its common brotherhood, than when standing upon the very brink of so cleaving asunder the foundations of the Human Family that the roof thereof should soon, in its vertiginous descent, crush all that lied beneath it. It was in this very context that the field of Development Economics first emerged, dedicated to comprehending not merely the Great Enrichment and the Industrial Revolution, but also how the Empire of Reason, which had seemed poised to conquer every corner of the Earth, could have culminated in the most irrational moment in all of human annals.

Condorcet, at the dawn of the Terror of the French Revolution – an analogous negation of the “cult of Reason” championed by its political exponents – in his Esquisse d'un tableau historique des progrès de l'esprit humain, published posthumously in 1795, would discourse that “progress”

is subject to the same general laws that can be observed in the development of the faculties of the individual, and it is indeed no more than the sum of that development realised in a large number of individuals joined together in society (Condorcet, 2012, p. 2).

The two great wars of the twentieth century, and the hundreds of other conflicts that did accompany them, would give us to understand, however, that instead of attaining maturity, Man was perchance regressing to a state of childishness, or else approaching his dotage. In Shakespeare’s play, the verses concerning the comedy of human life unfold into a beautiful reflection upon the “seven ages” of all human beings, and it seemed, to many, that we had arrived at the very last:

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

The keen lights of academia turned their focus towards the ‘underdeveloped world,’ which, in response to Europe’s self-wrought destruction, raised its collective voice, demanding its rightful place at the great table of nations. Were Europe to survive this generalised belligerence, it would find itself under the necessity of redemption. The ‘developed world,’ rather than ‘kicking away the ladder’ so that others might not ascend to its lofty plateaus, would be obliged to embrace a new, salvific mission, under the sway of a novel, globalist humanism, centred upon reforming the very foundations of international relations as hitherto known, so as to transition from the paradigm of global competition to that of global cooperation. It was in such a context that Paul Rosenstein-Rodan’s famed thesis of “balanced growth” was brought forth, formulated upon the relatively self-evident insight that ‘decisions of industrialisation’ on the part of a firm, or indeed any other ‘economic agent,’ are contingent upon the decisions of others. As Hirschman summarised:

Industry must not get too far ahead of agriculture. Basic facilities in transportation, power, water supply, etc. - the so called social overhead capital - must be supplied in adequate volume to support and stimulate the growth of industry. … Therefore, it is argued, to make development possible it is necessary to start, at one and the same time, a large number of new industries which will be each others’ clients through the purchases of their workers, employers, and owners. For this reason, the theory [was called the] theory of the ‘big push’. But such a process is given up as hopeless by the balanced growth theory which finds it difficult to visualize how the ‘underdevelopment equilibrium’ can be broken into at any one point. The argument is reminiscent of the paradox about the string that is equally strong everywhere and that therefore when pulled cannot break anywhere first: it either will not break at all or must give way everywhere at once. However, as Montaigne pointed out in considering this paradox, its premise ‘is contrary to nature’ for ‘nothing is ever encountered by us that does not hold some difference however small it may be’ (Albert Hirschman, 1959, pp. 51-52).

Ironically, for Hirschman, this theory did ground its analysis of radical differentiation between two economic units, autarkic and self-contained, and thus non-communicating, one ‘modern’ and one ‘traditional’, upon the distortions wrought by imperial colonisation:

… the balanced growth theory reaches the conclusion that an entirely new, self-contained modern industrial economy must be superimposed on the stagnant and equally self contained traditional sector. Say’s Law is here made to reign independently in both economies. This is not growth, it is not even the grafting of something new onto something old; it is a perfectly dualistic pattern of development, akin to what is known to child psychologists as “parallel play.” There are indeed instances of this kind of development, but they are usually considered conspicuous failures from both the social and economic points of view: the contrast between the Indian communities of the Peruvian altiplano and the Spanish mestizo economy along the coast comes to mind and so do the much decried enclave-type plantations and mining operations that have been set up in several underdeveloped countries by foreign concerns as perfectly self-contained units, far away from the danger of contamination by the local economy (Albert Hirschman, 1959, p. 52).

The world-system that bound colonies to their metropoles was not premeditated as a means of developing the conquered regions. This became manifest through the creation of specialised enclaves dedicated to exportable commodities, which required no contact whatsoever with pre-existing modes of life for their subsistence. Celso Furtado, for example, would demonstrate in his classic Formação Econômica do Brasil (1958), during his post-doctoral studies at the University of Cambridge, that a long-standing impediment faced by the erstwhile Portuguese colony in its industrial development was the lack of ‘primitive capital accumulation,’ for the money generated within the economic units of export-led agriculture did not circulate within Brazilian territory: the sugar mills were erected with Dutch loans, their parts fabricated in Lisbon or Amsterdam; slaves and beasts of burden were employed in production, receiving no wages; and the mill owners saw no requirement to purchase the luxury goods that adorned their conspicuous idleness in the rising townships around them, preferring instead to import such articles directly from the Old World. The currency, thus, departed almost as swiftly as it was produced. There was scarcely any ‘multiplier effect’ or transmission of this form of planned capitalist economy that might integrate the diverse regions of Brazil: the plantations communicated not amongst themselves; the City and the Countryside were divided by an impregnable barrier of interests.

Yet Hirschman reminds his readers, directly thereafter, that development need not unfold in such a manner. Citing Perroux directly, he states that “growth poles” can induce subsequent investments through a “chain of disequilibria” (Albert Hirschman, 1958, p. 65). The balanced growth approach was preposterous because

it combines a defeatist attitude toward the capabilities of underdeveloped economies with completely unrealistic expectations about their creative abilities. On the one hand, the conception of the traditional economy as a closed circle dismisses the abundant historical evidence about the piecemeal penetration by industry that competes successfully with local handicraft and by new products which are first imported and then manufactured locally. It also disregards the evidence that, for better or for worse, some products of modern industrial civilization - flashlights, radios, bicycles, or beer - are always found sufficiently attractive to make people stop hoarding, restrict traditional consumption, work harder, or produce more for the market in order to acquire them. But, on the other hand, a people that is assumed to be unable to do any of these things and that is therefore entirely uninterested in change and satisfied with its lot is then expected to marshal sufficient entrepreneurial and managerial ability to set up at the same time a whole flock of industries that are going to take in each others’ output! For this is of course the major bone that I have to pick with the balanced growth theory: its application requires huge amounts of precisely those abilities which we have identified as likely to be in very limited supply in underdeveloped countries. … In other words, if a country were ready to apply the doctrine of balanced growth, then it would not be underdeveloped in the first place. … if ten projects could be undertaken jointly, lending each other mutual support in demand, any one of them would be more profitable than the same project undertaken in isolation. On the premises stated, this is undoubtedly correct. But it is also true that a country cannot undertake any number of projects just because they would turn out to be profitable if it undertook them (Albert Hirschman, 1958, pp. 53-55).

The problem, in its entirety, resided in a flawed philosophical perspective regarding the very meaning of development:

development means transformation rather than creation ex novo: it brings disruption of traditional ways of living, of producing, and of doing things, in the course of which there have always been many losses; old skills become obsolete, old trades are ruined, city slums mushroom, crime and suicide multiply, etc., etc. And to these social costs many others must be added, from air pollution to unemployment … (Albert Hirschman, 1958, p. 56).

Even in more refined variants of the doctrine, which deduce from the observation that “atomistic private producers cannot appropriate the external economies to which their activity gives rise” that, perforce, all investment would needs be “centrally planned,” the problem persists:

Assumption of responsibility by the state in the economic field has most frequently been urged not to provide more impetus to development through the adding up of all the gains, but to introduce some of the social costs into the economic calculus and thus to temper the ruthlessness and destructiveness of capitalist development. Presumably the advocates of this course thought that some sacrifice in the speed of the process of creative destruction would be well worth while if it could be made a bit less destructive of material cultural, and spiritual values. And, admittedly, a major difficulty to the speedy industrialization of today’s underdeveloped countries consists precisely in the fact that they are not prepared to incur those social costs that were so spectacularly associated with the process during the early nineteenth century in Western Europe. They are forcing their young entrepreneurial class (as well as their taxpayers in general) to internalize a good portion of these costs through advanced social security, minimum wage, and collective bargaining legislation, through subsidized low-cost housing and similar “welfare state” measures (Albert Hirschman, 1958, p. 57).

In this same paragraph, Hirschman casts doubt upon the validity and utility of the thesis of absolute internalisation by the State, and his own proposal for development, founded upon the idea of “unbalanced growth,” shares great similarities with that advocated by Perroux since the 1930s, which the Frenchman termed the “strategy of (re-)organisation of markets.” Hirschman emphasizes that

… nonmarket forces are not necessarily less “automatic” than market forces (Albert Hirschman, 1958, p. 63).

For him, the prevailing view within the literature concerning ‘mechanisms of correction’ or of ‘adjustment’ for the imbalances in relative prices created by the development process, suffered from an excessive narrowness. The “monotonous regularity” with which authorities intervene under public duress, whenever market forces have shown themselves wanting in addressing economic problems perceived by those who suffer most grievously from them, would be proof that

we do not have to rely exclusively on price signals and profit-maximizers to save us from trouble (Albert Hirschman, 1958, p. 64).

Both markets and the State are, for Hirschman, valuable means for the potential correction of developmental disequilibria. For him, the notion that there must be either perfect planning for development to take flight, or perfect markets for it to be possible, is “not only impractical but also uneconomical.” For Hirschman, it is clear that it is not necessary for all imbalances to be corrected, chiefly because, often, they may stand as living proof that the process of “development” effectively implemented by a government, a junta, or an elite is inhumane and disregards the volitions of the people subjected thereunto:

But if a community cannot generate the “induced” decisions and actions needed to deal with the supply disequilibria that arise in the course of uneven growth, then I can see little reason for believing that it will be able to take the set of “autonomous” decisions required by balanced growth. In other words, if the adjustment mechanism breaks down altogether, this is a sign that the community rejects economic growth as an overriding objective (Albert Hirschman, 1958, p. 64).

Development cannot (or rather, ought not) be imposed, be it by bureaucrats or by entrepreneurs. The paramount reason for this is that there is no means by which to define “universal needs” (save, maybe, for the most basic of all, bread and water) to justify such an imposition: every perceived need is historically and culturally produced, and therefore arises from the experience, values, beliefs, and perceptions of human beings – not hypothetical, utilitarian, rational, and ‘maximising’ agents – whose existence is constituted by linguistic, ritualistic, and relational inheritances, from which each one constructs his own understanding of himself. In a work of 1963, Journeys Toward Progress, Hirschman would echo Adam Smith and other luminaries of the Scottish Enlightenment, attributing the cause of this anxiety – this eagerness to demand that others adopt more ‘rational’ habits and consumptions, in accordance with ‘their own interests which they ought to be capable of comprehending’ – to a difficulty in perceiving the slow transformations of ‘preferences’ – many of which arise unforeseen – that occur at a rhythm and on a timescale foreign to our presentist and decontextualised perceptions, incapable as we are of grasping the nuances of consciousness in persons who have lived through circumstances incomprehensible to those unfamiliar with them. For example, Hirschman says that

It may appear strange that large masses of men should elect to live in an area where they know they will be exposed to complete loss of livelihood several times in their lifetime. Brazilian writers have explained the puzzle by opposing the risky but free life of the sertão to the oppressively organized life on the coastal sugar plantations, with its many reminders of the not-so-defunct slavery (Albert Hirschman, 1963, p. 35).

Citing Thorstein Veblen, Hirschman recalls that human beings function upon the basis of an ‘entrained will,’ reminiscent of the volitions of their formative community. Contrary to the commonly diffused notion that “necessity” is the “mother of all invention,” Capitalism, he avers, had already furnished us with sufficient proof that it is “invention which is the mother of necessity” (Albert Hirschman, 1963, p. 68). This citation reveals the absence of a unidimensional view of development in Hirschman, for all the noxious compulsions of consumerism may thus be more pointedly criticised as distortions of true development. This cultural cognisance on Hirschman’s part is made explicit by one of his citations in the footnotes:

The fulfillment of one need establishes conditions out of which others emerge … In most instances it is impossible for people to foresee [these emergent wants] even if they try … Entrained wants are a consistent feature of motivational stresses for cultural change (Barnett, 1953, p. 148).

Finally, it remains to be noted that in Hirschman, one of the reasons for the general preference in underdeveloped countries for strategies such as balanced growth is the twofold geopolitical and internal pressure upon ‘latecomer societies’ to

… attack a variety of problems regardless of whether their resources, abilities and attitudes are in harmony with the tasks they are undertaking. Perhaps we can place into this category most of today’s underdeveloped countries with their ‘revolution of expectations’ and their compulsive desire to solve all problems of economic, social, and political backwardness as rapidly as possible. In this case, the lag of understanding behind motivation is likely to make for a high incidence of mistakes and failures in problem-solving activities and hence for a far more frustrating path to development than the one that characterizes the industrial leaders (Albert Hirschman, 1963, p. 312).

A portion of this anxiety stems from the systematic deterioration of the terms of trade between countries at differing levels of Gross Domestic Product, one of Perroux’s most innovative diagnoses for his era – later to become fundamental to Centre-Periphery theories and the Latin American developmentalist school.

2.2 The Influence of the “Austrian School”

In Germany, Perroux studied under several of the foremost economists of the German Historical School, such as Werner Sombart, and political philosophers of the stamp of Carl Schmitt. I possess not sufficient textual foundation to digress upon the influence of either of these two worthies on Perroux’s thought, and shall therefore confine my attention to his sojourn in Austria. This is because, some thirty years thereafter, our author would yet make reference to the existential dilemmas that the science of economics was then traversing in the Österreich, the Eastern Realm. The pupils of Carl Menger, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, and Friedrich von Wieser, in the City of Music, would not only cast doubt upon the scientific rigour of neoclassical theory, but would also endeavour to call into question the technocratic pretensions of the neoclassical economists.

Just as the fall of the great Austro-Hungarian Empire raised a cloud of blown dust, which hung suspended like a spectre, hovering over all Europe, with soft sighings that seemed to announce that the Age of Empires was yielding place to the Age of Nation-States, so too did the melancholy of the Austrian intellectuals disperse itself across the globe, imposing a great burden upon the new directions that economics was to take once the great wars had concluded. Whosoever hath the ears of his heart inclined closely to his sight will readily note in Perroux’s prose the sound of a whistle, faintly sibilant between his lips as he marshals his typewriter, trilling, stubbornly and unperceived, that same doleful melody of the Viennese sceptics, who cried with apprehension and resignation even whilst maintaining the stiff posture of “defenders of Liberal Civilisation” (I commend to the reader the truly beautiful book by Erwin Dekker on this subject, The Viennese Students of Civilization: The Meaning and Context of Austrian Economics Reconsidered, to which I shall dedicate a review upon this Substack in due course).

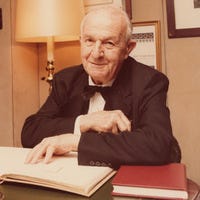

In Austria, Perroux became part of the prestigious circle of Ludwig von Mises and attended the lectures of Sigmund Freud. If imaginative freedom and prosaic licence permit me to employ a language other than that proper to the historian, I should venture that Perroux likely attended in a somewhat distracted manner the public soliloquies of these two great masters. I say this not merely because, in the 1930s, Mises was yet burnishing his art of churlishness – it is easy to conclude that, for this, he required constant practice, and who better than young, newly-graduated foreigners upon whom to vent his fits of temper – only thus could Mises, a decade later, officially become (yet another) of the more embarrassing members of the Mont Pèlerin Society, by disrupting the elegant hubbub that arose from the discussions, amidst mutual laughter and incredulity, that Milton Friedman, Friedrich von Hayek, Fritz Machlup, George Stigler, and Lionel Robbins were enjoying during dinner, having proclaimed in a loud and clear voice, whilst striding with hurried and noisy steps towards the door: “You are all a bunch of socialists!”; nor do I say it because the father of psychoanalysis, by 1934, had long ceased to water the flower of his youth, having, at that time, dedicated his energies to better expounding how, metaphorically, the metastasis that had been spreading from his mouth to his chest for ten years – and against which he fought with pertinacity, with as many surgeries as cigars – reflected the malaise of Civilisation, so ineluctable that not even the most honest prayers of homo religiosus could assuage it, a subject that must have caused considerable discomfort to a young, deeply devout Catholic such as Perroux.

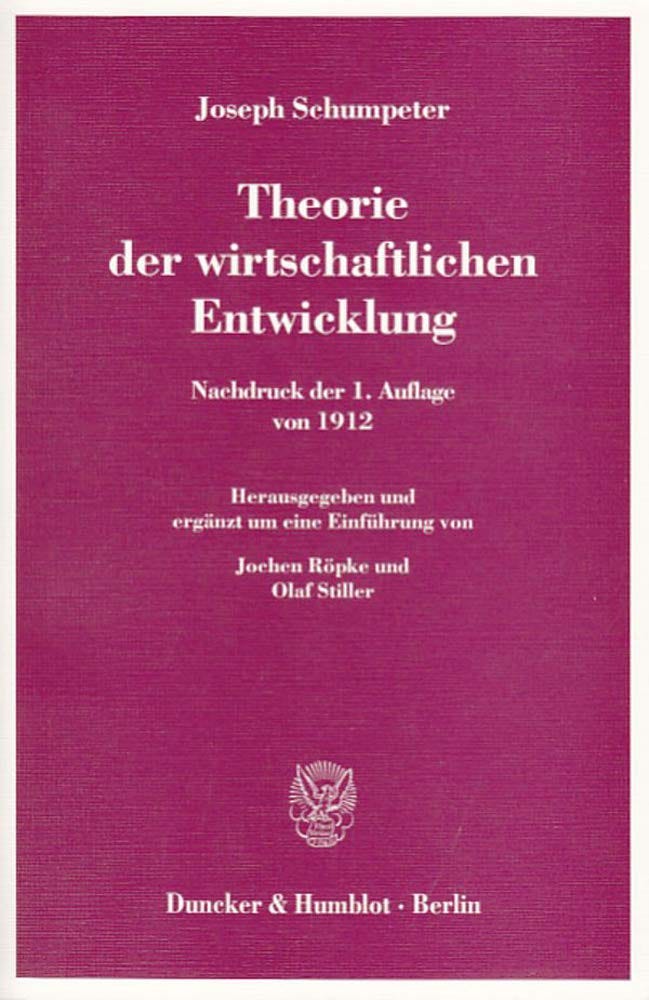

Nay, the reason for which I mention this possible distraction is another, more comical one, a reason emanating from a mind – my own – which has, thus far in this text, no commitment to the veracity of the facts: I allude here to that distraction a man must cultivate if he wishes to preserve his dignity when, having found his one great love, by life’s misfortunes and unpredictable turns, he has had to content himself with those other paramours who consented to make love to him at least… Joseph Schumpeter, another great economist trained in Law and one of the most constant references in the Works of Perroux, had, since 1932, been lecturing at Harvard. Having essayed upon several other occasions to make his acquaintance, the meeting betwixt the two would only come to pass decades thereafter, when the renowned author of disruptive innovation and creative destruction dispatched an invitation, co-authored by Edward Chamberlin – for whom Perroux likewise harboured a transatlantic admiration – for the Frenchman to present his thesis of ‘growth poles’ at a lecture in the United States.

Proof of this may be found in the fact that Perroux, a short while later, would pen the introduction to the French edition of Schumpeter’s Theory of Economic Development (originally published as Theorie der wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung in 1911). But even if it be reasonable, therefore, to conjecture that Perroux would have preferred to encounter Schumpeter, his time in Vienna was not spent in vain. The Freudian interest in the ‘psychology of crowds’ did not pass unobserved by the French economist, who would come, as we shall see, to define ‘economic development’ as a process contingent upon ‘mental and spiritual’ changes within a people. Of these two encounters, however, Freud appears to have left fewer imprints upon Perroux's Oeuvre (truth be told, the aforementioned volume, Aliénation et Société Industrielle, dating from the 1970s, does abound in references to Freud). Perroux, shortly before serving in the so-called ‘French mission’ of academics who would come to found the University of São Paulo (USP), penned the preface to the 1935 French edition of Mises’s Socialism (originally published in 1922 as Die Gemeinwirtschaft: Untersuchungen Über Den Sozialismus), the very tome that ignited the Economic Calculation Problem (also known as the Socialist Calculation Debate).

The principal lesson that Perroux drew from his suppers and sing-songs with the Mises Circle at the Gruener Anker restaurant was that it would be a matter of technical impossibility in principle – and therefore not solvable even by the world’s most powerful computing engine furnished with a GPT∞ – for the State to control all modes of production and distribution within an economy by determining their relative prices, irrespective of the conclusions drawn from the static models of perfect equilibrium by Oskar Ryszard Lange, Fred Manville Taylor, and Abba Ptachya Lerner, which purportedly had proven the theoretical possibility of the functioning of ‘market socialism’ – ceteris paribus, evidently.

The ‘socialist neoclassicals’ would note, with a certain measure of irony, that none had contributed more to the development of their theses than Mises himself. The challenges which the Austrian presented to the possibility of determining prices in an economy where all means of production were collectivised by the State were treated as exceedingly stimulating playthings, awakening a veritable contest amongst academic economists: who would discover the most elegant and simple mathematical solution to the economic calculation problem? Lange and Taylor went so far as to declare that Mises ought not to be seen as the father of Neo-Libertarianism – now embraced by finance bros such as Javier Milei, who endeavour to make of the State the world's largest billboard, even to the extent of promoting cryptocurrencies via the official government Twitter account instead of the Argentine Peso, its principal instrument of Sovereignty. Nothing of the sort! Mises, they contended, should be viewed as one of the patriarchs of Scientific Socialism for his pioneering role in transforming Marx’s unnameable dream into veritable blueprints:

A statue of Professor Mises ought to occupy an honorable place in the great hall of the Ministry of Socialization or of the Central Planning Board of the socialist state (Lange and Taylor, 1964, pp. 57-58).

Perroux, however, remained steadfastly beside sceptics such as Don Lavoie. In 1985, Lavoie published a historical review of the paths taken by the debate (Rivalry and Central Planning: The Socialist Calculation Debate Reconsidered). Therein, the professor from George Mason University explored the Marxian Oeuvre extensively, only then, with exceeding confidence, to raise the question: were Mises and Hayek truly answered by the mathematical model of general equilibrium proposed by the ‘market socialists’? Or is it, as is more common in the history of great controversies, that if one were to take the introductory propositions and then read the conclusions consecrated by economic science, one would not find oneself faced with a flagrant non sequitur?

Don Lavoie’s point may be thus summarised: it was not enough, as all well know, that economists were incomprehensible to most normal folk; it was not enough, Heaven help us, this “truth universally acknowledged” – borrowing here, quite brazenly, the opening phrase of Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice (1813) – that “in conversations about Economics” it is but a matter of time until “no one any longer knows what is being spoken of,” as Michel Houellebecq so aptly puts it in Sérotonine (2019); nay, to make matters worse, not only do the content and form appear incomprehensible to outsiders, but they are also so to the very practitioners of the field themselves! Different Schools of Economics may very well speak different tongues and fail to comprehend one another:

The fact that the neoclassical interpreters of the calculation debate shared [an] essential analytic background only with the economists on one side of the debate may be sufficient reason to suspect that the other side has yet to have been adequately understood. Differences between the neoclassical and Austrian interpretation of such key concepts as “economic theory”, “efficiency”, “ownership”, and “price” led the neoclassical chroniclers of the debate to consistently misinterpret the arguments that the Austrian economists were trying to make, and to do so in remarkably similar ways (Don Lavoie, 1985, p. 3).

But Perroux was a polyglot! Having learned from both sides, the French economist attempted – by fits and starts, admittedly – to transcend neoclassical microeconomics as a whole, denying it the status of a true scientific method for human behaviour. In one of his most audacious assertions, Perroux sharply averred: “economic science up to date masters not even the notion nor the theory of competition” (Perroux, 1964, p. 96). It is hardly surprising, therefore, that in the same section, Perroux congratulated Friedrich Hayek for having presented all his colleagues in the profession with a great dilemma:

Et qui ne sent la difficulté où nous introduit F. Hayek quand il distingue entre l’ordre concurrentiel (competitive order) qui « fait fonctionner la concurrence » et la concurrence ordonnée ou organisée (the so-called ordered competition), qui, presque toujours, tend à restreindre le caractère effectif (effectiveness) de la concurrence? (François Perroux, 1964, p. 96).

[And who does not sense the difficulty into which we introduce F. Hayek when he distinguishes between the competitive order which "makes competition work" and ordered or organized competition, which almost always tends to restrict the effective nature of competition?]

In his 800-page tome, L’Économie du XXème Siècle (1961), Perroux wove a grandiloquent critique of the blindness induced by the lens of static analysis, which, by viewing Economic Development as a series of photographic captures, would forgo the sight of that which dynamic models were capable of comprehending: the inherent inequalities in every process of economic transformation, an aspect most dear to the theses of the Austrian School:

Il faut, sur ce point, donner entièrement raison à F. Hayek quand il écrit: « La concurrence est par nature un processus dynamique dont les caractéristiques essentielles sont éliminées par les suppositions qui sous-tendent l’analyse statique. » Ou encore: « Elle est un processus qui implique un continuel changement dans les données et dont la signification, par conséquent, doit être nécessairement manquée par une théorie qui traite ces données comme constantes (Perroux, 1964, p. 106).

[On this point, we must agree entirely with F. Hayek when he writes: “Competition is by nature a dynamic process whose essential characteristics are eliminated by the assumptions underlying static analysis.” Or again: “It is a process which involves a continual change in the data and whose significance, consequently, must necessarily be missed by a theory which treats these data as constant.”]

But his solution differs from that of Mises, for Perroux does not entirely exclude the participation of the State in the process of price formation (be it national or international). In the aforementioned book, whose essays were penned in the immediate post-war period and contain a vast repository of critiques concerning the formation of the European Union and the Marshall Plan, Perroux strives to formalise his theories, proposing his own model of dynamic (dis)equilibrium; an incomplete endeavour which caused him much frustration – in this sense, his critical self-awareness ought to have led him to concur with current commentators, who have ceased to draw inspiration from him, deeming his approach “too fuzzy to be characterized”. Even having surrounded himself with competent mathematicians to develop his work – which explains the change of name of the Institut de Science Économique Appliquée (ISEA), founded by him in 1944, to the Institut de Sciences Mathématiques et Économiques Appliquées (ISMÉA) – the modelling and applicability of his most revolutionary theses did not arrive in due time, for when he published Unités Actives et Mathématiques Nouvelles: révision de la théorie de l’équilibre économique général (Active Units and New Mathematics: revision of the theory of general economic equilibrium) in 1975, others, such as Albert Hirschman, had already built upon his foundations and gained the attention of governments and economics departments across the globe.

Before, however, we proceed further in this brief history of the intellectual antecedents to Perroux’s theory of development, whose basic presuppositions were presented here, it is needful to mention what, more precisely, the Frenchman inherited from Schumpeter. Still in the introductory part of his book, we may gain a better notion:

L’effet de domination ne peut pas être « tiré » logiquement des prémisses rigoureusement exprimées de l’équilibre général formulé à partir des conditions de l’interdépendance générale et réciproque … Une dynamique complète peut être tirée de l’effet de domination. Le jour où elle serait entièrement élaborée, elle mériterait peut-être le nom de dynamique de l’inégalité, comme la dynamique de J. Schumpeter pourrait s’appeler dynamique de la nouveauté. Tandis que celle-ci oppose les mécanismes de l’innovation à ceux de la routine, celle-là opposerait les mécanismes de la domination à ceux du contrat sans combat (Perroux, 1964, p. 36).

[The effect of domination cannot be logically drawn from the rigorously expressed premises of general equilibrium formulated from the conditions of general and reciprocal interdependence... A complete dynamic can be drawn from the effect of domination. The day it is fully developed, it would perhaps deserve the name dynamic of inequality, just as J. Schumpeter’s dynamic could be called dynamic of novelty. While the latter opposes the mechanisms of innovation to those of routine, the former would oppose the mechanisms of domination to those of the contract without combat.]

Schumpeter’s Theory of Development emphasised, precisely, the disruptive effects of the innovation process within Capitalism. Contrary to the theses developed principally by North American economists, which became known as “Balanced Growth”, Schumpeter could not have been clearer: economic growth is, in itself, a disequilibrating phenomenon; it disturbs that which was, until then, established; it generates uncertainties in the same measure that it opens paths previously inconceivable, precisely by interfering with routines, with expectations, with the habitual course of the present. Growth is the fruit of changes in the expected future, changes these which affect the lives of all, positively or negatively. Perroux would note, however, that this process is not merely unbalanced, but also unequal. It is precisely in the inequality of growth’s effects that lies the possibility that growth cannot necessarily be considered “economic progress”; therein lies the key to comprehending competition: it generates the omnipresent possibility of conflicts within the movement of economic transformations.

Both the Schumpeterian and the Perrouxian notions can only be well understood – not merely grasped – through dynamic models that precisely emphasise the limits of our comprehension regarding economic growth, owing to the unpredictable diffusion of information, actions, and ideas which is its engine, given that “the agents of growth” are individual members of societies whose productive and distributive matrix is undergoing alterations. The difference between this conception of development and the more famous conceptions of the era, not only at a theoretical level but also at a normative one – that is to say, reflecting overly mechanical and insufficiently human conceptions of the development process – was very well illustrated by Hirschman in the preceding section.

Bibliography

Albert Hirschman (1959), The Strategy of Economic Development, Yale University Press, New Haven.

_________________(1963), Journeys Toward Progress: Studies of Economic Policy-making in Latin America, Twentieth Century Fund, New York.

Alexandre Mendes Cunha (2021), ‘Third-WayPerspectives on Order in Interwar France: Personalism and the Political Economy of François Perroux’ In Alexandre Mendes Cunha & Carlos Eduardo Suprinyak (eds.), Political Economy and International Order in Interwar Europe, Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, pp. 59-92.

Barnett (1953), Innovation: The Basis of Cultural Change McGraw-Hill, New York.

Condorcet (2012), Political Writings, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Don Lavoie (1985), Rivalry and Central Planning: The Socialist Calculation Debate Reconsidered, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

François Perroux (1954), L’Europe Sans Rivages, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris.

_______________ (1964), L’Économie du XXème Siècle, 2nd ed., Presses Universitaires de France, Paris.

_______________ (1967), A Economia do Século XX, 2nd ed., Herder, Lisboa.

_______________ (1970), Aliénation et Société Industrielle, Éditions Gallimard, Paris.

_______________ (1975), Unités Actives et Mathématiques Nouvelles: révision de la théorie de l’équilibre économique général, Dunod, Paris.

Oskar Lange & Fred M. Taylor (1964), On the Economic Theory of Socialism, McGraw-Hill, New York.