François Perroux and the ❝the heritage of human civilization❞ (I)

Remembering a forgotten economist

*This is the first part of the text François Perroux and the “heritage of human civilization” to be published bit by bit*1. Who was François Perroux?

I did commence this present Substack by remarking that the beginning of my Doctoral studies has been a considerable solace, and I have written down such sentiments chiefly because one might reasonably have conjectured otherwise, given the prevailing conditions within the Academy today. Allow me now to address the matter from a more personal vantage: to pursue my PhD with the certainty that, week upon week, I shall be instructed by two of Brazil’s most eminent intellectual historians of economic thought is, I must say, a truly splendid fortune. I will attempt to interview these gentlemen for my Podcast, Synesis: History of Ideas. The first one is Hugo da Gama Cerqueira, one of the foremost scholars responsible for the historiographical re-evaluation of Marx’s Oeuvre in Brazil; and Alexandre Mendes Cunha, my own esteemed supervisor and, I may venture, a burgeoning friend, who is a specialist of great repute in the ascendancy of Germanic Cameralism, in the economic thought of the Luso-Brazilian Empire, and—as I have but recently discovered—an assiduous reader of theories of Development created in the twentieth century.

Their initial lectures were, in a word, masterful, gracing a modest chamber, occupied by a select few privileged scholars, with the manifold subtleties that the application of contextual intellectual history to the exceedingly vast, yet lamentably seldom perused, Oeuvre of François Perroux is likely to bring. The ensuing disquisition, I must apprise the reader, represents a departure from the diaristic style I have hitherto employed, and it shall serve to crystallise both the notes I have diligently taken in the lecture-room and those gleaned from my reading of certain texts written by the French economist—a work, I confess, undertaken with some haste, for, much to the sorrow of Michael Oakeshott, education in our times has indeed become a “race in which the competitors jockey for the best place” and has long since ceased to be a tempered “conversation”. In this, the first part (I) of the essays I intend to devote to the thought of Perroux, I draw principally upon the instruction of Professor Alexandre, one of the few contemporary historians to have acquainted himself with the greater portion of Perroux’s published pieces. Moreover, Professor Alexandre was the very first scholar to consult Perroux’s personal archive, recently made accessible to the public in the environs of Caen.

Perroux was, it must be said, a controversial economist—as perhaps all economists are wont to be. The judicious exercise of those deductive faculties, infused into the Soul by the Universal Clockmaker—who, alas, finds Himself regrettably without employ since Mr. Steve Jobs, in his wisdom, outsourced the manufacture of his iPhones to the Foxconn establishment in Shenzhen (what an antinomy indeed!)—compels one to inquire, first and foremost: is it conceivable that an individual who, as an adolescent, elected to pursue the study of economics; who, in his youth, persisted in that course; who, in maturity, laboured as an economist; and who, in his declining years, prided himself for belonging to the same esteemed company as Milton Friedman, John Maynard Keynes, and, dare I say, myself—is it conceivable, I ask emphatically, that such a one could be entirely sound of mind?! The cosmic statutes that govern human conduct through the passions, impelling men, much like sister forces to gravity, to inflict harm upon themselves and others, inevitably and without any recourse to free will, do never prevaricate: nope! Yet, herein lies a curious, perchance even salvific, peculiarity concerning Perroux: he was not, in fact, a student of economics! Oof, it’s hard to contain a comforting sigh. His academic peregrinations commenced at the Faculty of Law in Lyon, where he achieved his baccalaureate, his masters’ degree, and ultimately his doctorate. It is a fact unknown to many nowadays, but the greater part of faculties strictly devoted to the economic sciences are of very recent establishment; since the seventeenth century, topics of Political Economy, and later of ‘pure economics,’ were taught as but one of the several branches of Natural Jurisprudence .

But upon learning that Perroux was a practicing Catholic, it would be an unheeding step to reprieve him from condemnation. For the generality of mankind, it is an arduous task to conceive of a Christian economist who does not, ere he retires to his slumber, recite the “Paul Johnson’s prayer”—so christened by Christopher Hitchens— in homage to the lustful American historian who, as if a pornographic angel was unstylishly flapping its graceless wings not in the condition of a witness but of a voyeur of human frailties, evinced a greater curiosity in the private actions of the great intellectuals of the Western Canon—what they did within four walls and what they concealed within their undergarments—than in taking the impertinent trouble to scrutinize their writings:

‘Fear of hellfire’, he told me, kept him in the Roman Catholic Church. He added that all the same he often broke the church’s commandments. I already knew that, or thought I did until he added wolfishly: ‘You see, I quite often pray for people to die’ (Christopher Hitchens, 1989).

It was not without reason, then, that the Lutheran economist Paul Heyne typed a celebrated essay entitled “Are Economists Basically Immoral?” as a companion to his renowned manual for undergraduate students, The Economic Way of Thinking (1980), nor that Ernst Friedrich Schumacher, an economist of both Buddhist and Catholic persuasion, felt himself compelled to publish one of the most striking titles in the annals of economics: Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered (1973). A measure of caution is ever prudent with gentlemen whose livelihood consists in discerning “trolley problems” wheresoever they look; a reticence doubly so, if they hold the view that the Almighty guides the fateful switch!

Though no evidence inclines us to surmise that Perroux recited such Johnsonian verses at his bedside before parting with Orpheus, we would be most premature were we to judge that, merely by virtue of not being an economist by training, he would, ipso facto, be a more humane economist by profession. Indeed, Alexandre’s lecture commenced with a monition: “Perroux, all evidence inclines us to believe, appeared to be a rather disagreeable individual.”

Notwithstanding the multitude of adversaries he may have accrued along his path, Perroux attained a certain global renown—though the author has, in our own times, fallen into comparative obscurity—and continued to occupy some of the most exalted positions within the French Academy almost until the close of the twentieth century. Such was his stature that, if he did not quite ascend to that Olympus inhabited by the foremost public intellectuals of his era, such as John Maynard Keynes (for whose Oeuvre he coordinated several principal editions in France), Albert Hirschman (with whom he frequently exchanged correspondence and citations), and Joseph Schumpeter (for whose theory of creative destruction he wrote the Introduction, adding to the Schumpeterian “innovation effect” the Perrouxian “domination effect”), he at least maintained a sufficient distance for his uncommonly long ears to remain untroubled by the irate protestations he incited in his rivals. He ascended, it is manifest, because his ambitions resided at an altitude surpassing even the lair of the gods. Having authored upwards of forty volumes and hundreds of articles over a career spanning sixty years, Perroux made invaluable forays into the most diverse realms of economic science, deepening debates concerning the application of disparate economic theories to international relations and the political (dis)utility of the economist.

The facet of his character that most piqued my interest was his resolute multidisciplinarity. Having delivered lectures in 1936 at the University of São Paulo (USP), the French writer garnered some prestige on Tupiniquim soil quite early in his career, and Brazil remains one of the few nations that preserves that Eliotic concern for extending an author’s life through the preservation of our memory of him (“…of the dead is tongued with fire beyond the language of the living…”).

His most renowned work is, in truth, a collection of previously published, albeit expanded, essays and articles entitled L'Économie du XXe Siècle (The Economy of the Twentieth Century), first published in 1961, wherein he presents his theses on development, distinguishing, with magisterial acumen, economic “progress” from economic “growth.” When one learns, however, that its publication followed closely upon one of his writings of greatest critical, normative, and stylistic liberty, Europe Sans Rivages (1954) (something along the lines of Europe Without Seashores)—a work never translated into Portuguese, comprising a most lengthy critique of the formation of the European Union and its perceived ‘isolation’ from the rest of the world—one is compelled to notice that L'Économie harboured an intention more elevated than merely describing the trends in global commercial relations subsequent to the great wars and the sprouting of Nation-States as fungi spreading their mycelia. In fact, Perroux drawn admirers precisely due to his higher inspirations, achieving parallel fame through other investigations of a non-economic nature.

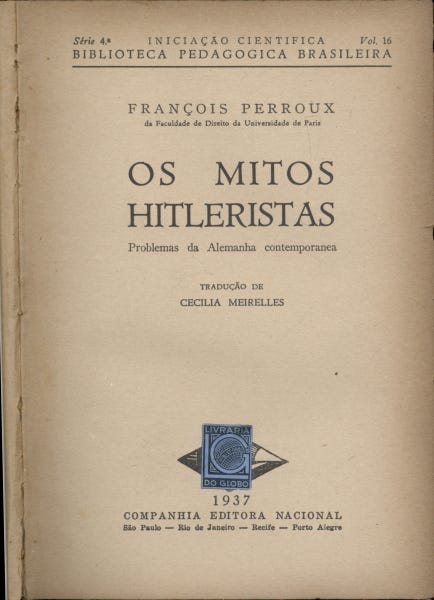

One of his best-selling books in Brazil, Les Mythes Hitlériens (Hitlerist Myths: Problems of Contemporary Germany), translated in 1937 by none other than the esteemed Brazilian modernist poet Cecília Meirelles, contested the historical aberrations propagated by Nazi ideology even before the invasion of Poland. Another much-discussed work was Le Pain et la Parole (Bread and Word) from 1969, which, according to an article published in Le Monde that same year, is a treatise of Catholic theology that endeavoured to transcend “structuralism as the natural philosophy of advanced technology,” purportedly responsible for “shattering Man”.

From an early juncture, as we shall further observe, Perroux harboured the aspiration to inspire a redirection of Technique to the service of human beings, rather than our becoming its thralls. This vision was defended with consummate skill in the conclusion of one of his most mature volumes, Aliénation et Société Industrielle (Alienation and Industrial Society) from 1970, a formidable philosophical and historical exploration of the concept of “alienation” concomitant with the advent of the Industrial Revolution, a work which denotes a decidedly more liberal spirit than that which one encounters in his writings from the interbellum period:

Les progrés des techniques de l’information et de la communication, la restructuration économique et politique des sociétés sollicitent l’invention par les esprits amis de la lumiére (animi et animae) — d’un oecuménisme du XXème siécle (Perroux, 1970, p. 180).

The progress of information and communication technologies, the economic and political restructuring of societies, call for the invention, by spirits friendly to the light (minds and souls)*, of a twentieth-century ecumenism.

*I am not versed in Latin. The translation is likely erroneous…

Literary and philosophical citations abound in his volumes, the bibliographies of which might well list Alfred Marshall, John Milton, Molière, and Gunnar Myrdal in immediate succession! It was from this intellectual miscellany, this profound concern for the “Complete Man” (l’Homme Complet, as he termed it) and not merely for homo economicus—whose demise he had ‘decreed’ half a century prior to Samuel Bowles—that his revolutionary Theory of Unbalanced Development emerged, acclaimed for its conceptualisation of “growth poles,” which remains to this day a seminal reference in Regional Economics.

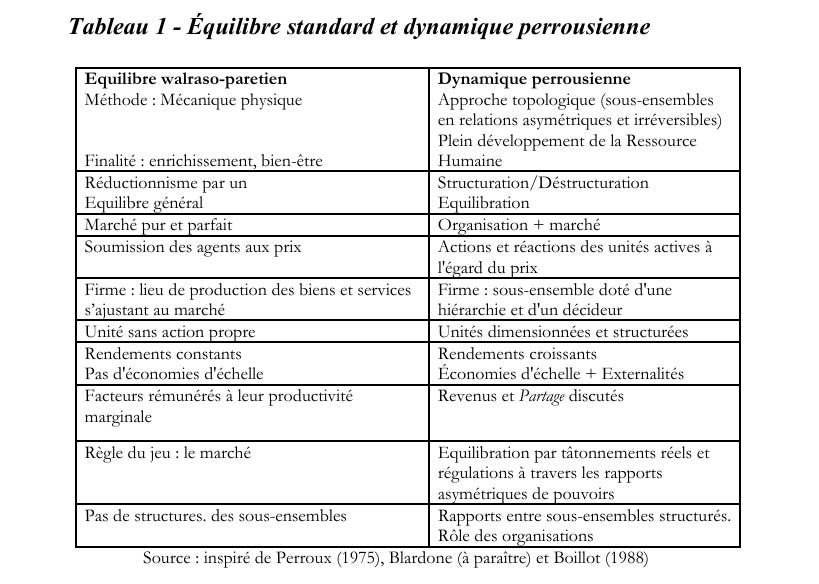

Before moving on to part 2, take a look at the table made by Philippe Hugon (2003), placing side by side the differences between the neoclassical approach to the study of economic development and François Perroux’s approach:

In fine, it is Perroux’s conviction that the prevailing models of perfect competition and, indeed, of general equilibrium, do serve to veil a more intricate problem which, until that time, afflicted the neo-classical theory: to wit, a systematic want of capacity for addressing the true dynamics of human relations, founded as it is not upon equality, but rather upon the unavoidable disparity between agents, regions, and States. With inequality posited as a fundamental tenet of the economy, the “actors of development” can be understood as striving to differentiate themselves, to become unequal, so as to transform their surrounding conditions - thus, the notion of ‘poles’ of growth, pulling up development given right circumstances and policies. Hereby, they provoke not merely disputes and rivalries amongst competitors, but veritable conflicts among humans of flesh and blood, between diverse regions occupied by one and the same people, or, indeed, between States. These conflicts, in their turn, owing to the widespread asymmetries, give rise to relations of domination, a concept which Perroux (1964, p. 33) defines as an agent or economic unit, styled A, possessing the power to exert an irreversible effect upon another, styled B, the latter lacking the capacity to impress a reciprocal transformation upon A in like measure. Above all else, it becomes manifest that Perroux holds there to be, within mainstream models of his time, a most fundamental problem of representation, forasmuch as they fail to consider that the encounters, disjunctions, and manifold effects of agents one upon another cannot rightly be apprehended as mere mechanical and automatic reactions:

L’équilibre général semble donc être tout autre chose que ce que l’on y voit souvent. Par lui-même, à lui seul, il n’est pas une représentation correcte de la vie des économies marchandes, ni une figuration satisfaisante des conditions d’optimum, ni même un moyen sûr de classer et de comprendre les changements. Il est un schème logique d'invention et de vérification qui exprime les tensions entre les activités des sujets et les exigences du tout qu’ils forment ensemble ; il produit une référence première et inéliminable, en statique ou en dynamique, en économie soit décentralisée ou régie par un plan, qui oriente les constructions mentales par quoi nous rendons peu à peu maîtrisables les incompatibilités qui opposent les projets humains à contenu économique. En conséquence, chaque fois que les relations entre sujets, entre adversaires, sont présentées comme des relations entre objets, entre contigus physiques, la fécondité du schéma est compromise (François Perroux, 1964, p. 13).

General equilibrium, therefore, appears to be a matter quite distinct from that which one is accustomed to observe in the real world [wherein “activities, with their onerous character, technique, which imposeth servitudes,” and the “global balance betwixt commodities exchanged” must all be taken into due account by the “central planner” no less than by “the free market”]. In its own essence, it constitutes an incorrect representation of the life in market economies, nor a satisfactory delineation of optimum conditions, nor, indeed, a sure means whereby one might classify and comprehend meaningful changes. It is, rather, a logical schema of invention and verification, which giveth expression to the tensions existing between the activities of individual subjects and the exigencies of the whole which they form together; it produces a primary and ineluctable point of reference, be it static or dynamic, within an economy either decentralised or planned, which, in turn, directs those mental constructions through which we may, by gradual degrees, render governable the incompatibilities that set human projects with their economic substance. Consequently, whenever the relations between subjects, or indeed, between adversaries, are presented as though they were relations between mere objects, or contiguous physical entities, the very fecundity of such a schema is thereby grievously compromised.

Upon analysing how such a model—possessed, as it is, of all its theoretical merits—doth nonetheless engender a true theoretical blindness when it becomes the sole method for apprehending economic subtleties through its ideal case, Perroux proposes that only a dynamic model, one steadfastly focused upon the omnipresent reality of the concentration of capital, is really capable of comprehending the actual vicissitudes inherent in the process of economic development. Only such a revision, he hoped, would illuminate the possible distortions to the true realization of ‘development’ that diverse plans may bring about, the genuine impediments which varied scenarios within international relations may cast before countries not holding sway, and, finally, the very impasses that so often beset the pursuit of all good and humane objectives of policy.

It would thus be perceived, Perroux suggests, that the earnest pursuit of international development must rely upon the active engagement of dominating nations, an engagement born, it is to be understood, of a greater human obligation. Moreover, it would, in this guise, be more readily acknowledged that the markets for labour and for goods are, by their very essence, political. Only by the incorporation into economic theory of credible postulations concerning power and dominion may the State be reconceptualised, so as to permit the moral advancement and the cultivation of the capabilities and faculties of those human beings entrusted to its care. To this end, Perroux comprehends that the State must possess the capacity to order its markets—not merely set the “rules of the game”—and its modes of production, in such a manner as to condition innovations, productive changes, transformations in technique, and, indeed, in the very spaces of socio-economic existence, directing them towards the ‘spiritual’ well-being of the people, for their fullest happiness and unimpaired dignity, and this without ever confounding mere ‘growth’ or ‘enrichment’ with that which constitutes true ‘progress’.

In the following section, we will trace the origins and context of his thesis.

*The complete bibliography will be made available in the final part.