JUDGE: “Do you judge me?

FRANZ: Shooks negatively his head.

JUDGE: “Do you have a right to do this?”

FRANZ: “Do I have the right not to?”— A Hidden Life, Terrence Malick

Introduction

Human history trudges under the weight of its own past, ploughing — whether by conscious intent or not — the virgin soil of uncharted roads.

Alexis de Tocqueville, in Democracy in America, observed with curiosity that the most enduring relics of even the most forgotten civilizations are their sacred tombs, and that complex, populous, and opulent societies often remain cradled within the bounds of their own origins. With commanding assurance, the French writer — enraptured by all he had witnessed in the United States — declared at the outset of his work that, just as men and nations bear the imprint of their beginnings (for the circumstances that swaddled and nurtured them in infancy shape every phase of their maturity), so too is the most lasting of all human achievements that which most faithfully reflects our end — our miseries, and the inevitable decay, ageing, and death that await us all.

Yet today I shall speak not of that historian, but of History herself. More precisely, I turn to one of her most vivid shadows: in the Vesuvian eruption of Modernity, few figures have cast so enduring a shape upon the last centuries as Martin Luther. Here there shall be no biography; my concern lies solely with the Political Philosophy of the Great Reformer.

Increasingly, we perceive in our world that Modernity’s attempt to purge all sense of the transcendent — if not quite stillborn — has shown itself at best utterly unnecessary. I shall neither condemn it here nor, as is too often the custom, bind Modernity blindfolded against a wall and parade a row of little wooden soldiers before it. My aim is simpler. Setting aside the manifold debates that surround this theme, I wish only to address one matter: in the quest for human emancipation, the road of disenchantment and total secularisation increasingly seems a dead end, and the cosy wayside inn supposedly awaiting at its terminus remains choked with the dust of time.

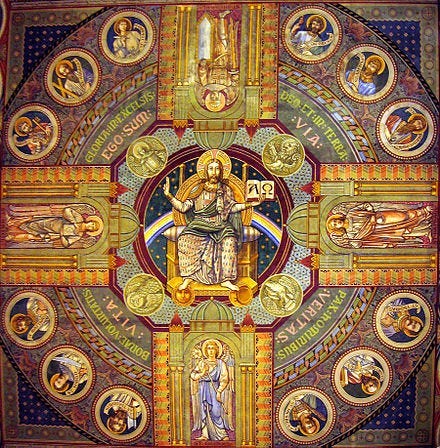

Whether that was indeed the principal route embraced by those who called themselves ‘modern’, whether we have irrevocably crossed a point of no return, or whether we ever truly set foot upon that path — borrowing Latour’s insight — all of that matters little here. Let us instead attend to the facts, leaving speculation at bay: God is returning with renewed vigour — in rhetoric and in practice, in public life and private devotion, in communal identity and individual conscience. It was inevitable that the curious would ask whence this phenomenon — so ancient, yet so startlingly new — had arisen, how it could revive, how the ember could blaze anew when all that seemed left was ash. Following the smoke, I beheld a cross aflame among the ruins of the Presidential Palace. I ventured to retrieve it from the wreckage, and among the many voices praising it I first attuned my ear to a single, commanding, courageous, robust cry in German. It was Luther. I asked him his thoughts on government and how he reconciled it with religion… What follows is what I understood of his reply.

Politics and Religion in Luther’s View

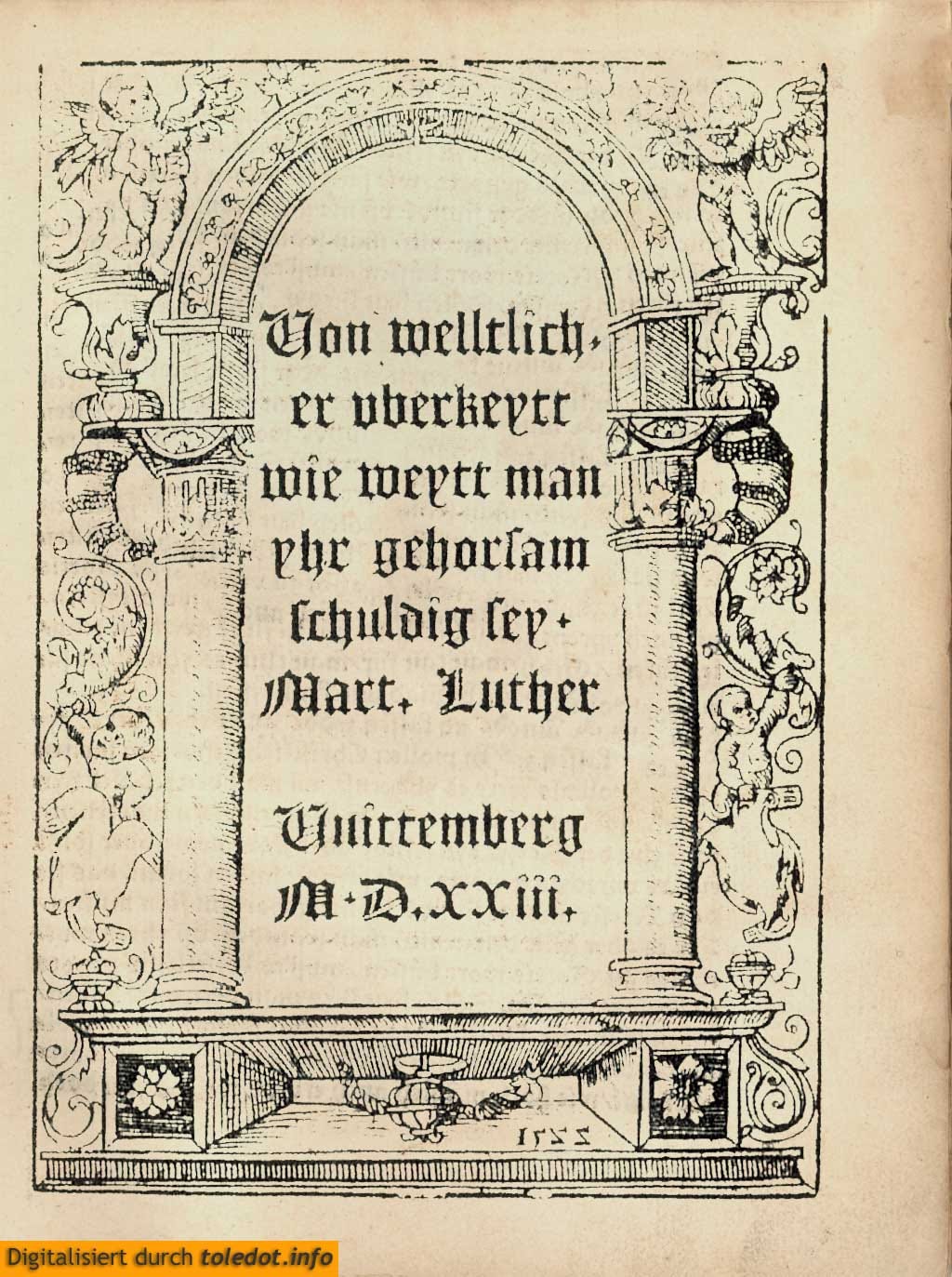

In his 1523 pamphlet On Secular Authority (Wie weit sich weltliche Obrigkeit erstrecke), Luther probes this theme with profound personal urgency. He penned the tract after enduring the fallout from his German translation of the New Testament: the hands of Saxon state officials were stained with fresh ink from the newly printed German Gospel. Unaccustomed to reading in their own tongue, they may have been confounded upon reaching Paul’s Epistles, concluding that ink-stained hands could only “be washed with blood”! Might Duke George himself have lacked even a rudimentary grasp of Latin, prompting him to seize the German copies in haste, eager at last to understand the words he had long heard at Mass but never fathomed? In any case, he issued an edict of confiscation under the guise of upholding the authority of the Holy See. Nothing could have influenced more deeply the writings of the ex-Augustinian than such self-interest; by hoarding the Sacred Book as one might amass worldly wealth, he inspired in all the envy and longing to discern what treasure it was that led a prince to claim the Scriptures solely for himself!

The encouragement bestowed upon Christ’s fervent servant by every censor was profound, and it is no small wonder that one finds in Luther’s writings a constant appeal to political arguments for tolerance and dissent.

In this brief treatise—penned in response to the edict commanding the seizure of every copy of his German New Testament—the Wittenberg professor champions the right to legitimate insurrection against both secular and ecclesiastical authorities. He argues for a clear and formal separation between spiritual and temporal governance and for the inviolable freedom of conscience, all set against a majestic biblical tapestry and delivered in an orality as expansive and impassioned as any sermon.

First, Luther assigns to religion and the clergy the care of souls, while reserving to the State the stewardship of bodies—often a necessary prelude to salvation of the spirit. True Christians, though rare, require no law but that of God, for they act justly, refuse to diminish their neighbours by always seeking to be the least, and bear all things with forgiveness.

Yet, as we well know, few disputes arise between two parties fully convinced of their own wrongdoing, nor does the sincere belief in one’s own righteousness lead two Christians into conflict over justice; the injured soul would accept the wrong, turning the other cheek as Christ taught. To Luther, such an ignoble predicament becomes a lesson in detachment from worldly strife.

Much as certain Buddhist monks extol in their reflective writings, we ought to give thanks for moments that treat us indignantly, for it is through these trials that our character is forged, our compassion for the fallen grows, and our inner strength is honed. But gratitude does not demand blind obedience to every command; it asks only that we accept whatever befals us with grace.

In this light, the calm and compassionate civil disobedience of Henry David Thoreau finds its precursor in Luther’s own analysis of a subject’s rights and duties toward his sovereign: no one is bound to commit injustice, and whatever befalls the believer thereafter, it is his burden to endure—and his neighbour’s to demand redress. For it is the duty of the community to see that justice is upheld. Far from an exhortation to lawlessness, Luther’s stance secures the collective force needed to defend the common good, so long as magistrates neither punish for private pleasure nor pursue ends other than the welfare of their people.

Finally, Luther declares that the Law exists for the unrighteous. As he notes, “the world and its throngs are not Christian and will remain so,” echoing Kierkegaard’s cry that “the crowd is untruth.” He recognises a self-destructive impulse in humanity’s passions and observes that, without the Law, society would hasten toward desolation.

Could true Christians, dwelling within the Kingdom of God yet surrounded by the Kingdom of Men, live in apparent anarchy without submitting to earthly statutes? Luther answers that it is through servility and love that believers willingly obey their rulers. By upholding secular authority, the sins that afflict the unregenerate are confined, and communal peace preserved.

The measure of a person’s perfection, Luther insists, lies not in rank or outward circumstance but in the heart—in faith and love. The greater one’s capacity for both, the higher one’s perfection. Nevertheless, he is keenly aware of the influence that external conditions exert upon the individual.

He discerns how wealth may inflame a tyrannical desire for dominion over the poor, as Adam Smith noted, and how miraculous it is when a prince rules justly, deriving no pleasure from his nation’s sufferings! He sees the ease with which pride disturbs a people’s peace, and the folly of coercing belief, which only deepens sin when the hesitant are forced into falsehood. Conscience, Luther reminds us, remains impervious to the sword, yet earthly burdens bend the knees of the weak and embolden the heel of the mighty.

Even if this state of affairs bears a place in the Divine Plan that Luther believes he has discerned—and though he admits it would be rash to judge too swiftly—his own experience does not prevent him from warning that, as a rule, rulers prove themselves the greatest fools and the vilest criminals upon the earth, from whom little good is to be expected—and indeed, one should ready oneself for the worst. Yet this conviction does not lead him to embrace the most accursed Liberalism of our age, which would confine religious experience to the innermost sanctuary of the soul.

The sovereignty of conscience stands as the very cornerstone of the Lutheran theological system, and yet public life, if it would be more peaceful, more orderly, more kindly, should allow itself to be suffused by Christian values and divine grace — without any contradiction of its political maxims. His consistency rests on the axiom that “it is right and necessary that all princes be good and Christian.” His point, expressed with gentle refinement, is that no prince may claim jurisdiction over the minds or souls of his subjects; yet this does not imply that politics, or any collective endeavour, suffers loss by an intimate alliance with religion. In an age when more and more voices call upon the State to recognize the beauty and significance of the transcendent in communal life, Luther’s thoughts offer a rich contribution to the debate—provided his critics do not reject them simply for advocating a particular form of transcendence.

In an ideal world, spiritual governance and secular authority would complement one another perfectly: one to shape the moral content of civic justice, the other to enforce peace and ensure the observance of basic rules of conduct. Luther discerns a certain mercy in the rigorous application of laws, so long as such enforcement occasions no greater injustice than that which it seeks to punish. By preventing a soul from tumbling into a life of vice, the State opens a space for the redemption that belongs to representatives of the Church. Since “the Christian performs every work of love without needing them himself,” the ideal State would become but an extension of that love — never imposing belief, yet reaping its noble fruits: for every deed born apart from love is condemnable, whether wrought by you, by me, or by an official of the government.

More than this, it would be a truly villainous, not loving, enterprise to seek to bind the individual conscience in chains. Secular authority cannot, even if it would, legislate the soul. Conscience is manifest solely to God, and so the Reformer perceives not only the futility but the impossibility of compelling belief by force. “Each man must decide at his own risk what he shall believe, and see that he believes rightly.” The shackles placed upon the body can never bind the thoughts. Force may warp the outward form, but it cannot touch the inward spirit. Let men err, Luther declares, that they may learn from their mistakes — let us permit their learning. Nothing is more regrettable than a person who delivers his understanding captive to another’s formulations, surrendering the duty of judging truths for himself. His appeal to experience recalls once more Adam Smith’s Lectures on Jurisprudence, where Smith wryly concluded that there was no need to forbid the Roman Catholic Church in England: a man too ignorant to discern the merits of Anglicanism need not be doubly punished. Heresies, when assailed by brute force rather than reasoned argument, only take deeper root and more broadly extend their sway over men’s wills. As freedom wanes, devotion to the “true faith” diminishes, and adherence to heresy flourishes.

Luther even goes so far as to link freedom of conscience with the prosperity of a nation. Governments that overstep their bounds and crush tolerance, he holds, will one day break the very necks of their citizens, reducing their lands and peoples to misery and want. An excess of legal severity thus yields the same ruin as its complete absence. “Woe unto thee, O land, whose king is a child,” laments Ecclesiastes. To admit the existence of divergent thought marks the maturity of any nation that aspires to peace and prosperity; yet Luther never fails to conceive of Christianity as the vital source of its vigour. One of Modernity’s clearest trajectories was first inscribed by the furious pen of a man crying out for his right to cry out. Law, though binding upon all, cannot wield the same rigor against the sick as against the sound, and can never stand above Reason, for it is from Reason itself that Law derives.

For the Great Reformer, then, conscience surpasses in worth every law and tradition — though it may be enriched by them — and nowhere does he deny this in his book. Reason must not be imprisoned by iron bars, by mere words, or by the will of another. And the great lesson he bequeathed — and which hundreds since have sought to embody in practice — may well be akin to that delivered by Saint John Chrysostom more than a thousand years before:

We bear no responsibility for persuading those who hear us, but only for offering counsel. […] Tell me, shall we not be ashamed if we abandon the salvation of our brethren […]? […] If each of us would take the hand of one neglected brother, you would swiftly advance the building up of us all (Saint John Chrysostom, 2022).

Yet, unlike Luther, Chrysostom discerns no mercy in punishment, nor does he believe that Christ would sanction it. The history of ideas remains in perpetual debate, just as every man wrestles with himself — whether he knows it or not. As Prudentius declared more than fifteen centuries ago in his classic poem Psychomachia, we are ever “waging war against the enemies of the soul, that is, the malignant passions.”

When we perceive that history bears many clear and gentle ideas, teeming and awaiting a fresh review, we find ourselves admiring paths once little trodden and recognising their hidden fertility. And when we lift our gaze forward again, a strange and beautiful convergence of courses emerges, offering new options to choose from: after each extended scrutiny, a decisive moment opens before us. Dissidence has never been extinguished, only silenced. The pursuit of absolute uniformity in human life is a manic nightmare, and every loosening of suffocating bonds first reveals heedless flights of freedom, before maturity calms the spirit and restores prudent behaviour.

We are left, then, to acknowledge our cradles and to accept our tombs, for when narratives die, history itself draws to a close.

In Luther’s age, the modern world suddenly surged upon humanity’s horizon of decision, yet it seemed firmly convinced that faith would continue to occupy the centre of modern life. This, of course, could only come to pass once the ideal was embraced that understanding and debate might one day become both habit and law—sheathing the sword ever more fully, surrendering its cold and futilely inhuman strokes.

Thus could the State begin to serve, rather than to be served.

Bibliography

Martinho Lutero (2005), Sobre a Autoridade Secular, WMF Martins Fontes, São Paulo.

São João Crisóstomo (2022), Riqueza e Pobreza: Sermões do Boca de Ouro São João Crisóstomo, Paz e Terra, Belo Horizonte