Why, really, is Economics a "Dismal Science"? (Introduction)

Thomas Carlyle influence in the USA, Asia and Latin America

1. Introduction: Carlyle’s global influence

The foregoing piece I published, entitled “Epistemic Intolerance Is Sophicidal”, was, in truth, but a prelude to essays such as this. Among the more disagreeable experiences I have encountered within Brazil was that of being compelled to justify myself before a professor who, with no small measure of irony, scoffed at my wish to pursue a master’s thesis on British liberal thinkers —“Do we truly require more studies on white Europeans?” he inquired. I am firmly persuaded that any soul who surrenders his studies entirely to the caprices of prevailing fashions is grievously lacking in that academic spirit which ought to animate all investigation; indeed, only a malformed personality could ever possess such servile pliancy. And were I already a professor, I should regard with a most sceptical eye any pupil who approached me absent of the faintest ambition of cultivating even a modicum of authenticity, who seemed content, rather, with whatever stale crumbs might fall from the edge of my desk.

If we are to be reduced to nescient labourers in the division of intellectual labour, working solely in the name of some end entirely extrinsic to the noble education born of arduous daily study — then, by all means, let us be replaced forthwith by artificial intelligence!

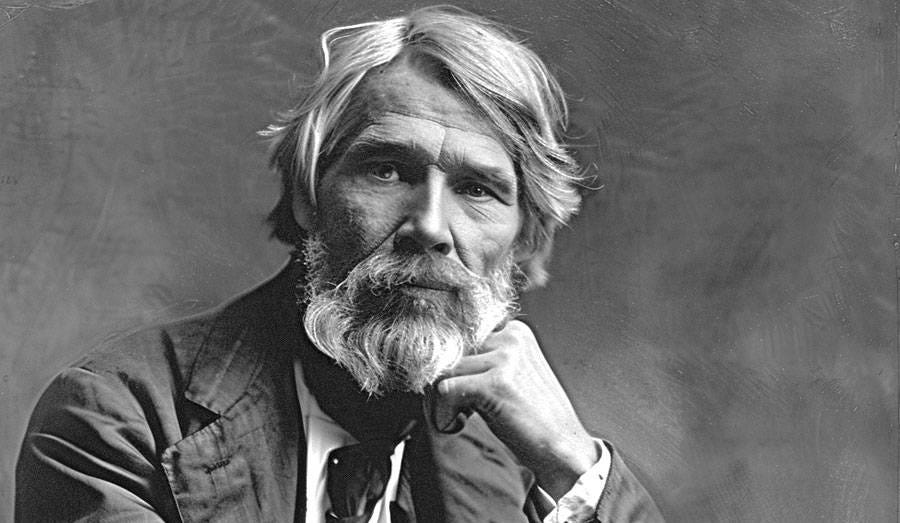

Perhaps such attitudes — as I do not contend they have yet become universal, nor do I feign that they contain much novelty — are attributable to the utter unfamiliarity in these parts with the figure of Thomas Carlyle. It is for this reason that, prior to addressing the question raised in the title, I take the liberty of introducing him to the reader yet unacquainted.

A quick search in Amazon Brasil’s website reveals that but one of his works has been recently rendered into Portuguese: a 2023 edition of On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History. A masterpiece of Victorian prose, Carlyle’s peculiar strain of ‘Romanticism’ intoxicated an entire generation of intellectuals around the world — hence even ‘indigenists’ as I ought to become, were they to upheld high standards of consistency, might well devote at least a measure of attention to such a ‘white European’ as he. His works were no idle ornaments of empire: they were active participants in the great transnational migration of ideas that characterised the nineteenth century.

Sartor Resartus (1834), his most celebrated philosophical romance, proved indispensable reading for an entire generation of English-speaking thinkers throughout that Long Century. Nor was it the elite alone who perused his pages! Carlyle’s books were devoured with fervour by Britain’s autodidactic workmen — including one such figure we shall shortly speak in the next post. Framed as the musings of a tailor, this curious novel unfolds as a kind of existentialist parable that affirms the boundless liberty of the human will to reject Evil and, by that very renunciation, forge a meaning for life — with no pandering to demagogic apologetics for religion. From these passages, not a few leaders of Britain’s early syndicalist movements drew their inspiration in forging the figure of the famed Working-Class Hero, who would rise to political leadership among their companions in the name of greater economic justice within industrial society.

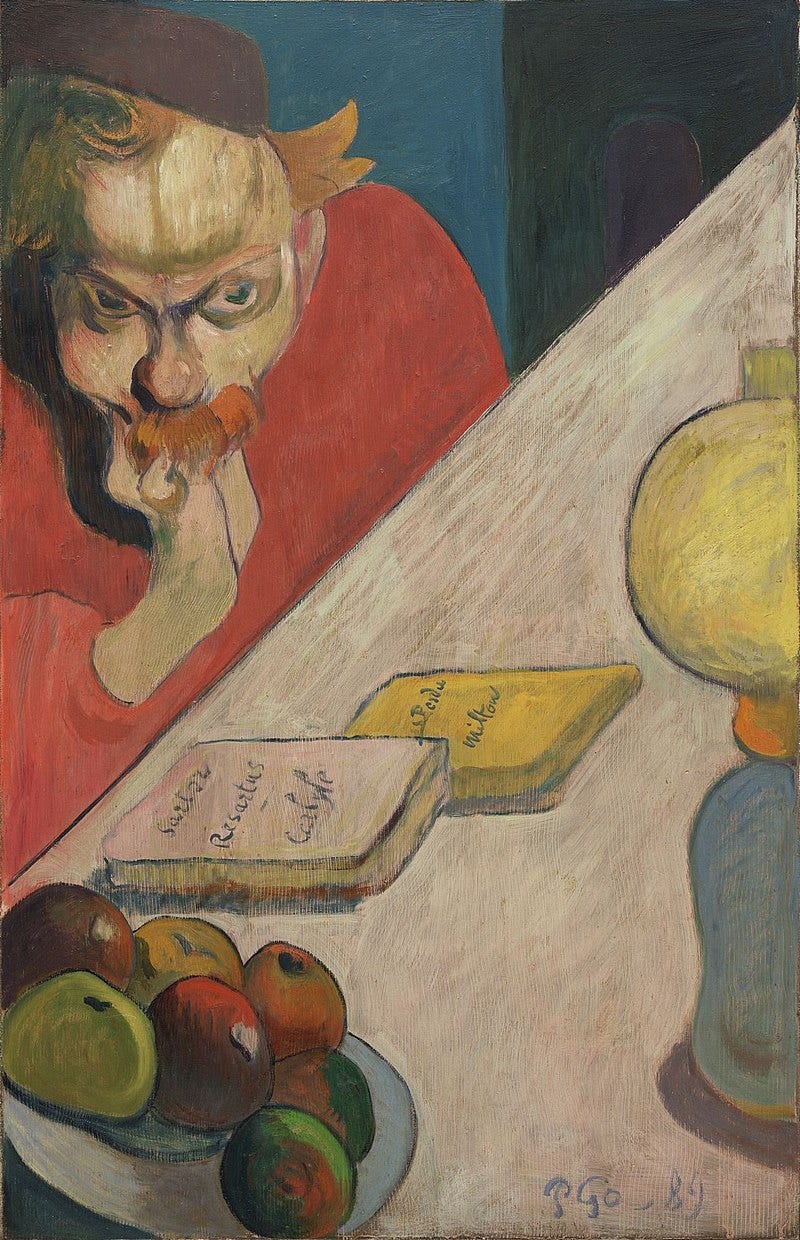

George Eliot, the nom de plume of the luminous English novelist Mary Ann Evans, once observed that Sartor Resartus had attained such renown that even those who “least sympathised with [Carlyle’s] opinions” could not but acknowledge the profound place the work had occupied “in the history of their own minds.” So deeply did its influence run that none other than Paul Gauguin would come, in time, to depict Carlyle in one of his paintings — a tribute as unexpected as it is telling, from the post-impressionist voyager of Tahiti to the Scottish prophet of Chelsea!

Yet Carlyle was not known solely for his literary prowess, but likewise for his labours as historian, philosopher, and political orator. Among his most impactful works one must cite his studies upon the French Revolution (1837), upon Oliver Cromwell (1845), and upon Frederick the Great of Prussia (1858). His prose is imbued with an iconoclastic vigour — complex, critical, and deeply unsatisfied with life as presently conceived — while also offering a prism that does not readily collapse into the narrow confines of hasty or programmatic ideological judgments.

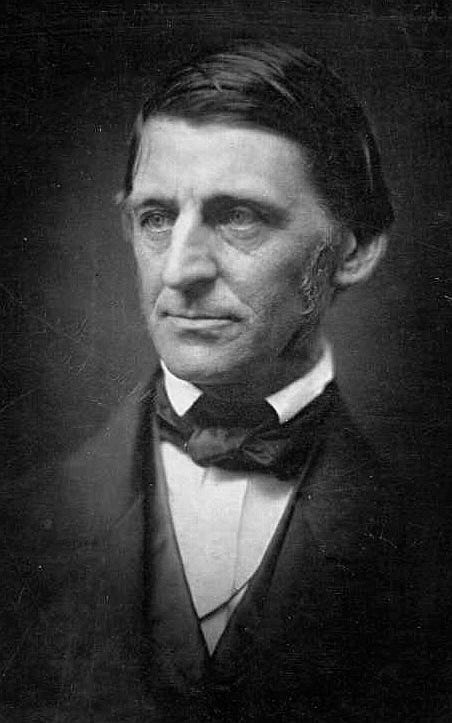

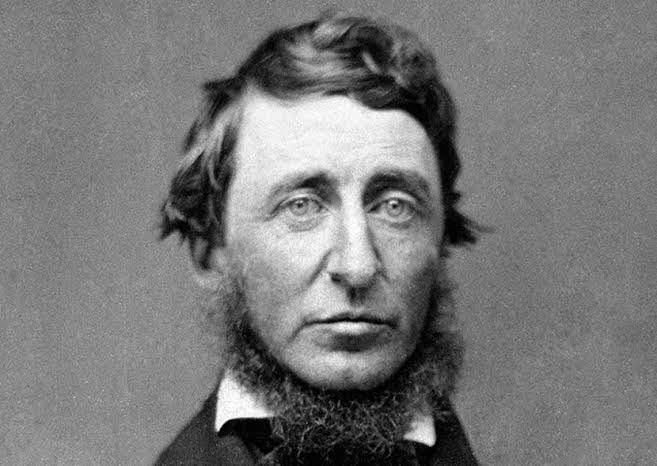

It is precisely for such qualities — despite the manifold flaws I should personally ascribe to certain of his ethical reasonings — that Carlyle afforded fresh vigour to the principal reformist generation of the United States: the so-called Transcendentalists, many of whom, as is well known, would go on to formulate the first doctrines of peaceful resistance or ‘non-obedience’ — precepts that would, in later years, inspire the likes of Dr. Martin Luther King and Mahatma Gandhi. Nor was his influence constrained to American shores alone: his spirit coursed through both nationalist and cosmopolitan movements across Europe, Latin America, and even Asia.

This, in and of itself, ought to cast a long beam of illumination down the avenues of inquiry concerning the appropriation of foreign texts and the praxis of reading some two centuries ago. Without lingering unduly — though the theme, I confess, fascinates me — I shall herein offer a few instructive examples.

1.1 The American audience

Certain remarks regarding the first volumes of Carlyle to disembark upon the shores of the ‘Land of Liberty’ speak most eloquently for themselves, as recorded by the historian Leon Jackson in 1999:1

I much question if Christopher Columbus was more transported by the discovery of America, than I was in entering the new realm which this book opened to me. … It became a sort of touch-stone with me. If a man had read Sartor and enjoyed it, I was his friend; if not, we were strangers. — Methodist Pastor William Henry Milburn.

What glorious views of man & life of God & destiny! … What force of language & grandeur of sentiment[,] what deep wisdom & living faith! I could sit forever at the feet of such a teacher! — Frederic Henry Hedge, Ralph Waldo Emerson’s friend.

Carlyle’s works are not to be studied - they are not to be re-read - the first impression is the truest and the deepest. If you look again, you will be disappointed and find nothing answering to the mood they have excited. — Henry David Thoreau thus wrote in his journal.

In Sartor Resartus, the protagonist journeys through what Leon aptly terms a “conversion narrative” — from a despairing, disoriented atheism to a resolute and spiritual regeneration. It was precisely the kind of tale that many in that age yearned to encounter. The intricate discourses Carlyle veiled behind the protagonist’s meditations on his own garments — thus weaving a “philosophy of clothes” whose grander aim was to afford a sweeping insight into the human condition — were not, in truth, the most rousing portion of his prose. As Leon elucidates, the chapters most enthusiastically cited in Boston upon the release of the book’s first edition formed a most convenient triad: “The Everlasting No!”, “The Centre of Indifference,” and “The Everlasting Yea!”

The reason readers settled on these chapters and read them so affirmatively, I believe, is because they offered a close, but transcendentalized, approximation of what Edmund Morgan has called the traditional Calvinist “morphology of conversion.” Morgan defines a morphology of conversion as a “natural history of conversion ... in which each stage could be distinguished from the next, so that a man could check his eternal condition by a set of temporal and recognizable signs.” Readers of Sartor evidently used Carlyle’s book in just this way, and were thus able to read their own spiritual anxieties and needs into Carlyle’s structural account of the conversion process, as it moved from despair to regeneration. As Frothingham argued, they made “Christian renunciation look attractive as well as obligatory.” (Leon Jackson, 1999, p. 160).

Carlyle was widely shared among young Americans, who took to heart the stirring and invigorating tenor of his prose, capable of “soothing the soul and elevating the senses,” through what Leon Jackson (1999, p. 159) termed a “highly selective appropriation” that emphasised the emotional resonance of the text far more than its political philosophy. This phenomenon stands as a prime exemplar of the plurivocality inherent in the circulation of ideas, which is never so readily grasped as a mere manifestation of a fixed, hieratic ideology bound within the strictures of a programmatic content.

1.2 The Asian audience

This section shall be the more concise, for the theme itself does not engage me sufficiently to warrant an extended inquiry into Carlyle’s reception throughout Asia. Yet I shall alight upon one unique case, so curious!

In a volume published in the year 2008, Hiroko Willcock delves into the influence exerted by Carlyle upon Uchimura Kanzo, one of the most distinguished Japanese pacifists of the pre–Second World War era, and founder of the Nonchurch Movement (Mukyōkai) — an indigenous evangelical Christian group from which emerged some of the foremost Japanese intellectuals of the age. Willcock styles him as a “Meiji Prophet and Carlylean Man of Letters.” To Kanzo — and indeed to various other religious and intellectual leaders such as Nitobe Inazo, Uemura Masahisa, Arishima Takeo, and Miyake Set’cho — Carlyle was nothing less than “the greatest preacher of righteousness” (Hiroko Willcock, 2008, p. 26).

His focus upon foreign authors sprang, in part, from a profound disappointment with the intellectual output of his own countrymen in that age. Amidst the pervasive “despair, uncertainty, insecurity, and poverty” and other afflictions that so grievously marked nineteenth-century Japan. Uchimura embraced

… the plight of Carlyle’s struggle against poverty, insomnia and isolation, as well as the struggle to find his own faith independent of any denomination, and free from formal, institutionalized, Christianity [to whom thought was the] life-fountain and motive-soul of action (Hiroko Willcock, 2008, p. 27).

Kanzo would thus come to draw inspiration from the portrait Carlyle rendered, with his clattering typewriter, of Oliver Cromwell — a leader depicted as one who “neglected formalism and regarded religious doctrines as oppressive,” ever exalting the liberty of conscience in all forms of worship. Uchimura’s own prose would gain renown for its terse moral aphorisms, whose stylistic genesis lay in Carlyle’s treatment of the French Revolution. It was, by the way, in Sartor Resartus that Uchimura discovered a

… new gospel of natural supernaturalism ... which elevated man and Nature into the domain of divine that replaced in their primacy the Calvinist God, the Bible, church and saints (Hiroko Willcock, 2008, p. 28)

from which he derived the foundational triad of his movement: Nature, Man, and the Bible. Justifying this selection as “the essential elements granted to mankind through the revelations of God,” Kanzo did not, like Carlyle, exalt “men and history to the rank of the divine,” but rather followed other Japanese authors of the period, such as Nakae Toju. Thus, Uchimura drank deeply from Carlyle’s work while retaining a “strong attachment to the moral and spiritual tradition of Japan.”

His historical writings on great figures of Japanese heritage followed the method of On Heroes, though they placed less emphasis upon the adoration of heroes. Kanzo treated these inspiring figures with far greater tenderness and humanity, seeing them more as models than as deities, and drew from his reflections practical solutions for enhancing the moral education of the Japanese people — an education which he deemed essential to the flourishing of the state (Hiroko Willcock, 2008, pp. 28–33).

Hiroko observes that Uchimura’s cosmopolitan stance — which extended his “nationalist Christian thought” toward a novel “conception of global nationalism, wherein the world would be as one great nation and Japan but a part of the whole” — was truly prophetic, standing in stark contrast to the parochialism that so often marked the rise of the Nation-State. In so doing, he prefigured support for the modern instruments of supranationalism (Hiroko Willcock, 2008, p. 37).

What ambivalent influences a figure such as Carlyle — now regarded by many contemporary scholars as “the father of Fascism” — was capable of exerting!

1.3 The Latin-American audience

A profoundly intriguing book — little discussed, as far as I am aware — which treats extensively the diffusion of Carlyle’s thought throughout Latin America is Redentores: Ideas y Poder en América Latina, authored by Enrique Krauze and published in 2011. Krauze presents the reader to the scottish writer laying hands upon a formula brimming with mediocrity: “Carlyle, el autor precursor del fascismo” [Carlyle, the author who prefigured fascism].

Such an introduction is apt to dishearten any serious reader of the nineteenth century, one familiar with the (intellectual and political) elitism that permeates the works even of such authors as John Ruskin or Matthew Arnold — whose writings are, nonetheless, so readily capable of inspiring a deep admiration for Social Justice in its redistributive form. While elements of resemblance may certainly be discerned between the regimes of Mussolini and Hitler and Carlyle’s notion of “hero-worship,” one must ever exercise great caution in wielding concepts so heavily laden with moral judgments — “of sentimentalisms”, valid as these may be in themselves, as Perroux would put it — when seeking to characterise an author, particularly if our intention be to apprehend, with honesty, his context and discursive performance.

In this regard, the quotations collected by Krauze also speak most eloquently for themselves; yet it is far from my intention to diminish the painstaking labour of that historian, who so deftly reanimates a complex cultural substratum, replete with ambivalences, stretching across Latin America from the closing years of the nineteenth century to the middle of the last. With great skill, he presents theses whose resonance has outlived the passing of time and now appear more compelling than ever.

His history of “redeemers” begins with Octavio Paz, who, in his youth, discerned in Marxism a path “redentor, heroico, suicida” [redemptive, heroic, suicidal] for Latin America, and pursued it with the eager joy of a Tancredi Falconeri. It then proceeds through a reconstruction of the ideological backdrop to Liberation Theology and the indigenous movements that sought to purge the land of imperialist blood — redeeming not only man from the evils inflicted upon one another, but likewise upon the living world that encircles them. At last, it arrives at the likes of Hugo Chávez, described as “un líder mediático, un predicador, un redentor por Twitter, un caudillo posmoderno” [a media leader, a preacher, a redeemer by Twitter, a postmodern caudillo].

In itself, such a study of the salvific ideals underpinning the idola theatri of our continent would suffice to recommend the work unreservedly. I shall write more about this volume in a future essay; for the moment, let us consider the curious influence that Carlyle exerted over the old Iberian colonies:

La oposición entre el régimen de la democracia y la alta vida del espíritu es una realidad fatal cuando aquel régimen significa el desconocimiento de las desigualdades legítimas y la sustitución de la fe en el heroísmo - en el sentido de Carlyle - por una concepción mecánica de gobierno. Todo lo que en civilización es algo más que un elemento de superioridad material y de prosperidad económica, constituye un relieve que no tarda en ser allanado cuando la autoridad moral pertenece al espíritu de la medianía. — José Enrique Rodó, 1900, a Uruguayan parliamentarian with great democratic feelings.

The opposition between the regime of democracy and the high life of the spirit is a fatal reality when the former regime signifies the disregard of legitimate inequalities and the replacement of faith in heroism — in Carlyle's sense — with a mechanical conception of government. Everything in civilization that is anything more than an element of material superiority and economic prosperity constitutes a relief that is quickly flattened when moral authority belongs to the spirit of mediocrity.

The Cisplatine essayist would, some years later, pen a panegyric to Bolívar in the Carlylean manner, proclaiming: “Bolívar es Héroe; San Martín no es Héroe. San Martín es grande hombre, gran soldado, gran capitán, ilustre y hermosísima figura. Pero no es Héroe” [Bolívar is a Hero; San Martín is not a Hero. San Martín is a great man, great soldier, great captain, illustrious and most splendid figure. But he is not a Hero]. Yet Krauze is unequivocal on one point: “Rodó no fue el único carlyleano de la historia intelectual latinoamericana” [Rodó was not the only Carlylean in the intellectual history of Latin America].

Francisco García Calderón, writing from Paris, published Les Démocraties Latines de l’Amérique (1914), prefaced by Poincaré — the future President of France. The work offered a political history of Latin America that “se apartaba del viejo republicanismo clásico” [departed from old classical republicanism] and reduced “la historia a biografía, propia de Carlyle” [history to biography, after the fashion of Carlyle].

To elucidate the rise of democratic forms on the continent, Calderón employed a dialectical method which opposed barbarism to civilisation, thus justifying, in certain circumstances, the use of force and the centralisation of State power as mechanisms of reorganisation within chaotic societies. His focus, however, is not so paradoxical as it might seem — for he did not discern latent tyrannies from nascent democracies in his analyses. Rather, he sought in even the most “constructive” and popular regimes those charismatic personalities who, more than “forging utopias,” were capable of imposing order amidst the social and political divisions that hampered governance in the wake of independence: men able to promote “democracias superiores, democracias del espíritu, no de la vulgaridad electoral” [superior democracies, democracies of the spirit, not of electoral vulgarity].

Writers of universal renown would soon breathe this same interpretive atmosphere:

La democracia es el caos provisto de urnas electorales — Jorge Luis Borges, who learned German, according to Krauze, after Carlyle’s own Germanophilia infected him!

Democracy is chaos provided by ballot boxes.

Even Juan Domingo Perón had recommended that Evita read one of his favorite books: On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History!

According to Krauze, dictators such as Hugo Chávez followed less the genealogical line of Karl Marx and far more the populist currents of the Left as derived from Thomas Carlyle — how curious indeed! Krauze’s detailed study even recalls one of Carlyle’s most renowned passages, wherein he draws a comparison between Bolívar and George Washington, so as to underscore the affinity between his mode of thought and that established in practice by the so-called “Bolivarian regime” in Venezuela — albeit in marked contradiction to some of the republican theses most cherished by Bolívar himself, who, ideationally, stood in far closer proximity to Edmund Burke than to Thomas Carlyle:

Pero más allá de su viñeta sobre Bolívar, la vigencia de Carlyle en el régimen bolivariano y, sobre todo, en la mente y la actitud de su líder máximo, está en el concepto del héroe como actor central de la historia (Enrique Krauze, 2011, p. 565).

But beyond his little essay about Bolívar, Carlyle’s relevance to the Bolivarian regime and, above all, to the mind and attitude of its supreme leader, lies in the concept of the hero as a central actor in history.

2. Thomas Carlyle as political commentator of Latin America:

I will bring here, just to save, a long quote that will close this part 1, excerpt Dr. Francia, commentary by the Scottish writer on José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia, the ‘founding father’ of Paraguay:

And Bolivar, “the Washington of Columbia”, Liberator Bolivar, he too is gone without his fame. Melancholy lithographs represent to us a long-faced, square-browed man ; of stern, considerate, consciously considerate aspect, mildly aquiline form of nose ; with terrible angularity of jaw ; and dark deep eyes, somewhat too close together, (for which latter circumstance we earnestly hope the lithograph alone is to blame) this is Liberator Bolivar : — a man of much hard fighting, hard riding, of manifold achievements, distresses, heroisms and histrionisms in this world ; a many-counselled, much-enduring man; now dead and gone : — of whom, except that melancholy lithograph, the cultivated European public knows as good as nothing. Yet did he not fly hither and thither, often in the most desperate manner, with wild cavalry clad in blankets, with War of Liberation, “to the death?” … With such cavalry, and artillery and infantry to match, Bolivar has ridden, fighting all the way, through torrid deserts, hot mud swamps, through ice-chasms beyond the curve of perpetual frost, — more miles than Ulysses ever sailed: let the coming Homers take note of it. He has marched over the Andes more than once; a feat analogous to Hannibal’s; and seemed to think little of it. … He was Dictator, Liberator, almost emperor, if he had lived. Some three times over did he, in solemn Columbian parliament, lay down his Dictatorship with Washington eloquence; and as often on pressing request, take it up again, being a man indispensable. Thrice, or at least twice, did he, in different places, painfully construct a Free Constitution … and twice, or at least once, did the people, on trial, declare it disagreeable. … Truly a Ulysses whose history were worth its ink, — had the Homer that could do it, made his appearance! (Thomas Carlyle, 1843 [1852], pp. 547-548).

Yet contrary to Krauze’s assertion, it becomes evident that Carlyle’s study of Latin America was not composed as a simple exaltation of Simón Bolívar. Quite the opposite!2 In his essay, Carlyle draws a pointed contrast between Francia and figures such as Bolívar, O’Higgins, San Martín, and Iturbide (whom he refers to as “the Napoleon of Mexico”), even though his analytic sobriety compels him to acknowledge that Francia’s dictatorship bore an “awful nature” and harboured a lamentable regard for liberty — “liberty of private judgment,” he writes, “unless it kept its mouth shut, was at an end in Paraguay.”

The former, Carlyle portrays as “poor South American emancipators.” Inspired, he claims, by Abbé Raynal and Constantin-François Chassebœuf, Carlyle depicts these great personages of Spanish American independence as preachers of the “gospel of Social Contract and the Rights of Man,” striving under exceedingly unfavourable circumstances — and thus, failing in their attempts to pacify and bring order to the Southern Cone. He even goes so far as to lampoon them, turning his wit toward one of the most crucial elements in the formation of modern nation-states: the National Library.

Whereas outstanding works — such as that of Nicola Miller, Republics of Knowledge: Nations of the Future in Latin America (2020) — attest that the Latin American independence movements pioneered the creation of chairs in Political Economy, the construction of libraries, publishing houses, and universities throughout the region — sometimes earlier even than in the European metropoles — Carlyle, however, mocks how little of this pioneering spirit proved, in his view, truly effectual or substantial:

Nay now, it seems, they do possess “universities,” which are at least schools with other than monk teachers: they have got libraries, though as yet almost nobody reads them, and our friend Miers, repeatedly knocking at all doors of the Grand Chile National Library, could never to this hour discover where the key laid and had to content himself with looking in through the windows (Thomas Carlyle, 1843 [1852], p. 550).3

Their collective failure can be seen by the depressing state of the people found there:

A people that uses almost no soap, and speaks almost no truth, but goes about in that fashion, in a state of personal nastiness, and also of spiritual nastiness, approaching the sublime; such people is not easy to govern well! (Thomas Carlyle, 1843 [1852], p. 550).

The Paraguayan people, he writes, were endowed with the same characteristics:

The Paraguay people as a body, lying far inland, with little speculation in their heads, were in no haste to adopt the new republican gospel. … Absurd somnolent persons, struck broad awake by the subterranean concussion of civil and religious liberty all over the world, meeting together to establish a republican career of freedom … are not a subject on which the historical mind can be enlightened. The historical mind, thank Heaven, forgets such persons and their papers, as fast as you repeat them. Besides, these Guacho populations are greedy, superstitious, vain. … Such men cannot have a history — though a Thucydides came to write it. (Thomas Carlyle, 1843 [1852], pp. 558-559).

Yet following Francia, the ‘average Paraguayan’ could read and write — though he was scarcely a “man of letters”. Carlyle notes that the dictator had effected “as many improvements as cruelties.” Francia introduced schools, reformed land tenure and improved agriculture, suppressed superstitions, ameliorated the justice system inherited from the Spaniards, and modernised Paraguay’s civil service: “peculation, idleness, ineffectuality, had to cease in all the public offices of Paraguay” (Thomas Carlyle, 1843 [1852], p. 562).

Described as a “Reign of Terror,” so unyielding as to earn from Carlyle the moniker of “the Dionysius of Paraguay” (in reference to Dionysius I of Syracuse), Francia’s regime, according to Carlyle’s account, delivered to the Paraguayan people precisely what they desired in the wake of the instabilities wrought by republican governance at the moment of independence:

To the eyes of Paraguay in general, it had become clear that such a reign of liberty was unendurable; that some new revolution … was indispensable. … The eyes of Paraguay, we can well fancy, turn to the one man of talent they have, the one man of veracity they have. (Thomas Carlyle, 1843 [1852], pp. 559-560).

Thus did José de Francia bring about “the notablest of all these South American phenomena,” albeit without deriving from it any particular pleasure:

What they say about ‘love of power’ amounts to little. Power? Love of ‘power’ merely to make flunkies come and go for you is a ‘love,’ I should think, which enters only into the minds of persons in a very infantine state! A grown man, like this Dr. Francia, who wants nothing, as I am assured, but three cigars daily, a cup of mate, and four ounces of butchers’ meat with brown bread; the whole world and its united flunkies, taking constant thought of the matter, can do nothing for him but that only. That he already has, and has had always; why should he, not being a minor, love flunkey ‘power’? (Thomas Carlyle, 1843 [1852], p. 562, quoting a Professor Sauerteig, while translating directly from German).

---

Indeed, at his death, the impression held by the people of him did not seem to brim with animosity. The funeral oration, delivered by a certain Reverend Manuel at Francia’s solemn obsequies, paraphrased the Book of Judges to proclaim that amidst the manifold social convulsions afflicting the political cauldron of Latin America, “the Lord, looking down with pity on Paraguay, raised up Don Jose Gaspar Francia for its deliverance.” Carlyle himself did not absolve Francia of inhuman deeds — and thus, the epithet “precursor of fascism” appears all the more staggering, unless we are content to throw into one and the same sack every past author who expressed some deference to aristocratic cosmovisions which, ere the rise of Liberalism, were near-ubiquitous throughout the world.

Carlyle, beyond any doubt, was not a “postmodern” anti-rationalist; quite the contrary. If Albert Camus was correct in declaring Nazism the apogee of nihilism’s ascent — the absurd sap of Power in the age of Modernity — then Carlyle stood firmly upon the solid ground of the religious ethics of his era. His political reflections were so widely read not in spite of, but precisely because of how modern they were: his theses resonated with the perceived necessities of nation-state-building, which reshaped sovereignty in the post-Baroque epoch that was Modernity’s very apotheosis.

Nazifascism, one might thus contend, represents the collapse, the downfall of that other branch of vitalist romanticism which, unlike its German counterparts, though also very spirited, was neither explicitly nationalist nor remotely eugenicist in the manner of Carlyle or Ruskin.

Bibliography

Enrique Krauze (2011), Redentores: Ideas y Poder en América Latina, Debate, Madri.

Hiroko Willcock (2008), The Japanese Political Thought of Uchimura Kanzō (1861-1930): Synthesizing Bushido, Christianity, Nationalism, and Liberalism, Edwin Mellen Press, Nova York.

Leon Jackson (1999), ‘The Reader Retailored: Thomas Carlyle, His American Audiences, and the Politics of Evidence’, Book History, V. 2, pp. 146-172.

Thomas Carlyle (1843 [1852]), ‘Dr Francia’ In Critical and Miscellaneous Essays, A. Hart, Philadelphia, pp. 547-568, disponível em Archive.Org.

Footnotes

1 https://www.jstor.org/stable/30227300?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

2 This interpretation is defended by Robert G. Collmer: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1032&context=ssl

3 https://archive.org/details/criticalmiscella00incarl/page/n557/mode/2up?q=bolivar